Click on graphic above to navigate the 165+ web files on this website, a regularly updated Gazetteer, an in-depth description of our island's internally self-governing British Overseas Territory 900 miles north of the Caribbean, 600 miles east of North Carolina, USA. With accommodation options, airlines, airport, actors, actresses, aviation, banks, beaches, Bermuda Dollar, Bermuda Government, Bermuda-incorporated businesses and companies including insurers and reinsurers, Bermudians, books and publications, bridges and causeway, charities, churches, citizenship by Status, City of Hamilton, commerce, communities, credit cards, cruise ships, cuisine, currency, disability accessibility, Devonshire Parish, districts, Dockyard, economy, education, employers, employment, environment, executorships, fauna, ferries, flora, former military bases, forts, gardens, geography, getting around, golf, guest houses, highways, history, historic properties, Hamilton, House of Assembly, housing, hotels, immigration, import duties, internet access, islands, laws, legal system and legislators, main roads, marriages, media, members of parliament, money, motor vehicles, municipalities, music and musicians, newcomers, newspaper, media, organizations, parks, parishes, Paget, Pembroke, performing artists, residents, pensions, political parties, postage stamps, public holidays, public transportation, railway trail, real estate, registries of aircraft and ships, religions, Royal Naval Dockyard, Sandys, senior citizens, Smith's, Somerset Village, Southampton, St. David's Island, St George's, Spanish Point, Spittal Pond, sports, taxes, telecommunications, time zone, traditions, tourism, Town of St. George, Tucker's Town, utilities, water sports, Warwick, weather, wildlife, work permits.

![]()

By Keith Archibald Forbes (see About Us).

In 1936, decades before Keith and his siblings were born, his father pioneered the radio direction finding system that was instrumental in commercial airlines flying into Bermuda and Keith's interest in Bermudiana began accordingly. His other files on Bermuda relating to aviation include Airlines serving Bermuda - Bermuda International Airport - US Military Bases in Bermuda from 1941 to 1995. Welcome to this special file on how these islands got their first aircraft, the men behind the initiatives, others who are etched permanently in Bermuda history, how Bermuda established several enduring claims to fame - and more.

![]()

A

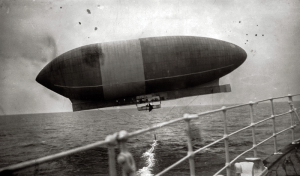

flight in an ungainly hydrogen-filled

blimp which ended in near-disaster off Bermuda. The airship “America”, long

consigned to footnote status by aviation historians, was the ambition of the six

adventurers — and one feline – involved in the attempt. Their

attempt to cross the Atlantic came just a decade years after the first

modern dirigible was launched and seven years after the Wright Brothers’ motorized glider

sputtered into the air at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina. American newspaper

publisher Walter Wellman also purchased a sturdy - subsequently famous -

lifeboat from an English firm in 1910 as he was preparing to attempt the first

powered flight across the Atlantic in the ‘America.’ In addition to its

basic role as a refuge for the crew should they be forced down at sea, the

lifeboat doubled as a kitchen, pantry, dispensary, smoking lounge and radio

position. It also served as a hiding place for “Kiddo,” a feline stowaway

discovered by Mr. Wellman and his five man crew after take-off on October 16,

1910 from New Jersey. The airship, its crew and the cat remained aloft for 38

hours, but were forced down just off Bermuda due to a combination of engine

problems and bad weather. Their salvation depended on crossing the path of a

Royal Mail Ship, the ‘Trent’, which (they) knew was sailing from Bermuda to

New York at the time. At 5 a.m. on the morning of October 18 Wellman

spotted the ship. Soon, the ‘America’s’ crew were communicating with the

‘Trent’ by Morse code and then by radio. After a hazardous operation, with

the airship being blown along at speeds of up to 25 knots, the lifeboat was

eventually lowered safely into the sea, complete with all crew, including the

cat. The airship, still airborne, and now considerably lighter, vanished over

the horizon. “The ‘Trent’ gave the crew safe passage to New York, where

they were welcomed as heroes. ‘Kiddo’ the cat was especially well received

and put on display in a gilded cage in the famous Gimbels department store. He

later went to live a quieter existence with Wellman’s daughter, Edith. The

adventure made front page news around the world.

A

flight in an ungainly hydrogen-filled

blimp which ended in near-disaster off Bermuda. The airship “America”, long

consigned to footnote status by aviation historians, was the ambition of the six

adventurers — and one feline – involved in the attempt. Their

attempt to cross the Atlantic came just a decade years after the first

modern dirigible was launched and seven years after the Wright Brothers’ motorized glider

sputtered into the air at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina. American newspaper

publisher Walter Wellman also purchased a sturdy - subsequently famous -

lifeboat from an English firm in 1910 as he was preparing to attempt the first

powered flight across the Atlantic in the ‘America.’ In addition to its

basic role as a refuge for the crew should they be forced down at sea, the

lifeboat doubled as a kitchen, pantry, dispensary, smoking lounge and radio

position. It also served as a hiding place for “Kiddo,” a feline stowaway

discovered by Mr. Wellman and his five man crew after take-off on October 16,

1910 from New Jersey. The airship, its crew and the cat remained aloft for 38

hours, but were forced down just off Bermuda due to a combination of engine

problems and bad weather. Their salvation depended on crossing the path of a

Royal Mail Ship, the ‘Trent’, which (they) knew was sailing from Bermuda to

New York at the time. At 5 a.m. on the morning of October 18 Wellman

spotted the ship. Soon, the ‘America’s’ crew were communicating with the

‘Trent’ by Morse code and then by radio. After a hazardous operation, with

the airship being blown along at speeds of up to 25 knots, the lifeboat was

eventually lowered safely into the sea, complete with all crew, including the

cat. The airship, still airborne, and now considerably lighter, vanished over

the horizon. “The ‘Trent’ gave the crew safe passage to New York, where

they were welcomed as heroes. ‘Kiddo’ the cat was especially well received

and put on display in a gilded cage in the famous Gimbels department store. He

later went to live a quieter existence with Wellman’s daughter, Edith. The

adventure made front page news around the world.

![]()

Under the command of Squadron Leader W. C. Hinks. She was finally commissioned on November 6, 1918, just before the armistice with Germany. From her evolved the R32 and much interest from the USA.

![]()

"What this Bermudian

did above

the battlefields of Europe as a Royal Flying Corps pilot flying for his

mother-country. Earlier, he'd been in the Bermuda Volunteer Rifle Corps, was one

of their contingent shipped to England to join Lincolnshire Regiment. From there

he was accepted by the Royal Flying Corps, later the Royal Air Force. A

formation of British machines had been carrying out some important operations

well over the German lines. On the return journey the weather suddenly became

hazy, and one of the pilots, Lieutenant Spurling, lost touch with the formation in the clouds. The

British pilot set his course due west, and flew on for some time. Having made

what he thought was sufficient allowance for the distance to the British lines,

he put down the nose of his machine and saw beneath him an aerodrome. The wind,

however, freshened considerably, and so far as covering the ground was concerned

he had been making only half the speed shown on airspeed indicator. As he

circled over the aerodrome, preparing to land, a German Scout machine suddenly

appeared from the clouds above him, and immediately to attack. Marveling at the

unusual temerity of the German in daring to attack over an English aerodrome,

the British pilot checked his descent and opened fire on his attacker. At this

moment he became aware that no fewer than thirty German machines were actually

climbing towards him from the aerodrome. Realizing now that he was over an enemy

aerodrome, he dived towards the first group of German squadrons, both he and his

observer firing on every machine upon which they could get their guns to bear.

The enemy pilots appeared too bewildered by the outstanding audacity of the

British airmen to attack them effectively at first, and their own tremendous

numerical superiority seemed further to confuse them. One German plane burst

into flames in the air, two more went down spinning and side slipping completely

out of control. Four enemy scouts had by this time got into position to attack,

clinging to the tail of the British machine. Two of these were sent blazing to

earth. Shaking himself clear of the remainder, the British pilot opened his

throttle and sped homewards leaving on that German aerodrome three blazing

wrecks, and two other crashed machines as a highly satisfactory outcome of what

might have proved a fatal mistake."

Lieutenant Spurling flew one of the new Sopwith Snipe aircraft. Manufacturer: Sopwith Aviation Company. Type: Fighter. First Introduced: 1918. Number Built: 497. Engine: Bentley B.R.2, 230 hp. Wing Span: 31 ft 1 in. Length: 19 ft 10 in. Height: 9 ft 6 in. Empty Weight: 1312 lb. Gross Weight: 2020 lb. Max Speed: 121 mph. Ceiling: 19,500 ft. Endurance: 3 hrs. Crew: 1. Armament: 2 machine guns.

![]()

Earlier, he'd been awarded another medal, the Star Trio. He was presented with the DFC for flying his bomber into the centre of a formation of some 30 German planes. He and his observer shot three down in flames and sent two others crashing to the ground. He had sent a postcard sent to his half-sister Ethel in Bermuda after he was injured twice on the front line. He and his wife had a daughter, Ilys Spurling Marsh, who was brought up at "Penarth", the family home in Rosemont Avenue. Her father rarely talked about his wartime experiences, including the heroics which led to his DFC. Her father, known as Rowe, was born in 1896 and joined the Bermuda Volunteer Rifle Corps in February 1915, sailing with the first war contingent for England in May and soon after being posted to the Lincolnshire Regiment. His 1916 postcard to Ethel describes how was "wounded in the hand" on July 3 and returned to the front to be "wounded in the foot and buried for a few hours" on July 13. He was commissioned in July 1917 and qualified for service in the Royal Flying Corps in September, before being posted to France and joining 49 Squadron in July 1918. His DFC was announced in the London Gazette on this day, in a report which described how he got separated from his formation and was attacked by a Fokker biplane at 2,000 feet. "Lt. Spurling then observed some 30 machines of the same type, heavily camouflaged; with great gallantry he dived through the centre of the formation, shooting down one machine in flames; two others were seen to be in a spin." Five of them then closed on his machine, but by skilful maneuvering, Lt. Spurling enabled his observer to shoot down two of these in flames. The three remaining aircraft broke off the combat and disappeared in the mist. A fine performance, reflecting the greatest credit on this officer and his observer." He returned a hero to Bermuda after the First World War and obtained his commission again in World War II, serving in Canada with RAF Ferry Command, where he was credited with unearthing a Nazi spy. He married Ilys Darrell in 1948 and ran a taxi service on the Island, as well as importing mushrooms and starting the Rowe Spurling paint supply company. He and his wife moved to Guernsey in the early 1970s but eventually sold up there with a plan to return to Bermuda. Instead, Lt. Spurling developed Alzheimer's Disease and died in a nursing home in England, aged 88. His body was flown back to the Island for a funeral at the Anglican Cathedral and he is buried in Pembroke.

Lieutenant Arthur Rowe Spurling in WW1 (left) and as a Royal Air Force officer in WW2 (right)

![]()

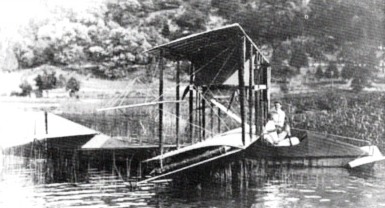

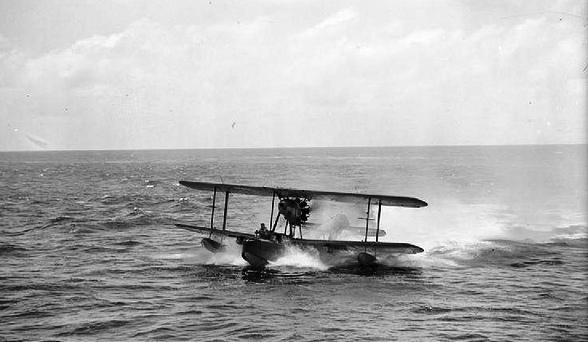

It was a Burgess-Curtiss N-9H Jenny, with registration number A-2646, powered by a Wright-Hispano 150 horsepower engine. It was a naval scout hydro-airplane that normally traveled on the deck of her mother ship the USS Elinore.

The aircraft had a gross weight of 2765 pounds and a top speed of 80 miles per hour. The 8725 ton cargo vessel was launched in 1917 as the General de Castelnau and was transferred from the US Shipping Board to the US Navy for war service. After the war, she had dumped gas drums and mustard gas shells in deep waters off Virginia. On this day, she was in the town of St. George after a scientific research voyage south of Bermuda, sheltering from bad weather. The Bermuda flight was not scheduled but poor weather made it happen. Bermudians got their first sight of an aircraft. At the Governor's request it was flown over the City of Hamilton Harbor by United States Navy Ensigns G. L. Richard and W. H. Cushing, They invited Governor Sir James Willcocks to accompany them and he accepted. He dropped from the open cockpit the first "Air Letter" posted in Bermuda. In front of a huge crowd he was rowed out to the aircraft waiting near the Royal Bermuda Yacht Club. Piloted by Richard, they were airborne at 12.45pm, flying towards Dockyard and returned safely to alight in the harbour at 1.30pm. A proposed further trip with his wife was abandoned after the engine began to play up. A total of 560 N-9s were built during World War I, most of which were "H" models. Only 100 were actually built by Curtiss. Most were built under license by the Burgess Company of Marblehead, Massachusetts. Fifty others were assembled after the war, from spare components and engines by the U.S. Navy at Naval Air Station Pensacola in Florida.

![]()

Flown by Captain John Alcock, Royal Air Force, and Lieutenant Arthur Whitten-Brown, Royal Flying Corps, who took off from St. John's, Newfoundland and landed at Clifton, Ireland in 16 hours and 12 minutes.

![]()

Spanning the length of two football (soccer) pitches, the flight was made only a few weeks after the success above of Alcock and Whitten-Brown. Among the 30 crew on board was 42-year old engineer George Graham from near Cupar, Scotland. The airship flew from East Fortune, Haddington, Scotland, the main Scottish airship base on the Firth of Forth, to Mineola, Long Island, New York, and back again. A northerly coastal route was decided on, in case the airship ran out of fuel for its engines. Two Royal Navy warships, HMS Renown and HMS Tiger, were used as supply vessels in case of difficulty, also to offer meteorological reports and if necessary to take the airship into tow. It was the first manned flight from anywhere else to the USA and was completed because of American interest in the airship. At that time, the USA had no experience with a rigid airship. The giant Royal Air Force/Royal Naval Air Service airship, gassed to its limit and loaded to its full capacity, was eased out of its shed by 700 members of the handling party. The engines were signaled to commence, the propellers roared into life and the airship was on her way to the USA with the strains of jazz coming from a gramophone. Hours later, it was discovered that a teenage crew member who was supposed to have been left behind because the dirigible was too heavy had stowed away on board. He also brought the ship's mascot, a tabby cat called Whoopsie. There were also two dogs. The airship arrived four days later, having traveled at an average 43 miles per hour, with only 140 gallons of fuel remaining. Before it tied up, Major Jack Pritchard, British Army, donned a parachute and dropped to the ground to become the first man to arrive in the USA from abroad by air. He did so because there was not yet any other way for the airship to be properly tethered to the ground and it was his job to organize it from the ground. The welcome from the USA made world headlines. The airship was in the USA for three days fore sailing back to the UK, not to East Fortune because of bad weather but to Pulham Air Station near London.

![]()

The achievements of the first transatlantic flight in a Vickers Vimy bomber, by Captain John Alcock, Royal Air Force, and Lieutenant Arthur Whitten-Brown, Royal Flying Corps, and first landing of an airship in the USA closely thereafter gave fresh impetus to aviation in Bermuda. Major Henry "Hal" Kitchener of the Royal Flying Corps - a nephew of Field Marshal Earl Kitchener of Khartoum and son of a former Governor, returned to Bermuda as a war hero. He teamed up with Major Hemming of the AFC, also a Great War aviator. They brought to Bermuda several aircraft most islanders had never seen before.

They were three Avro 504K sea planes, two 2-seat Standard planes, a three seat model and three four seat Supermarine Channel Mark 1 flying boats. The two men wanted to make Bermuda a base for aeronautic surveys of Newfoundland in Canada and in Central and South America. Among their exclusive rights was one to spot whales from the air, to create a revival of Bermuda's once-dominant whaling industry. They selected Hinson's Island, which Major Kitchener owned after 1920, as their base and built two wood framed hangers there. They also built a slipway to serve both hangers. The slipway had rails to move the aircraft to and from the water. But their plans were ahead of their time. Their aircraft (right) were distinctive sights above the skies of Bermuda. They were fuelled by the Esso Company's West India Oil Company's wagons that put their cargoes of fuel on boats to make the crossing across Hamilton Harbor to the aircraft's' terminal on Hinson's Island. The aviation company did not survive for long. However, in its heyday it was the way many Bermudians got their first flight in an airplane - and it provided the talk of the town for many weeks. Bermudians had to wait 17 more years before they could fly to another jurisdiction.

![]()

They were G-EAFF, G-EAEG and G-EAEJ, all still with their military colors, similar to the one shown above. They arrived by ship and joined the Avro aircraft of Bermuda and West Atlantic Aviation for sightseeing tours of Bermuda. They were based at Hinson's Island. The "Short" flight was for 10 minutes to Gibb's Hill Lighthouse then back to Hinson's Island; the "Middle Tour" was for 20 minutes, over Spanish Point, North Shore. South Shore; the "Grand" Tour over most of Bermuda; and "Special Charter" included stops. One of the latter was for the actress Pearl White.

![]()

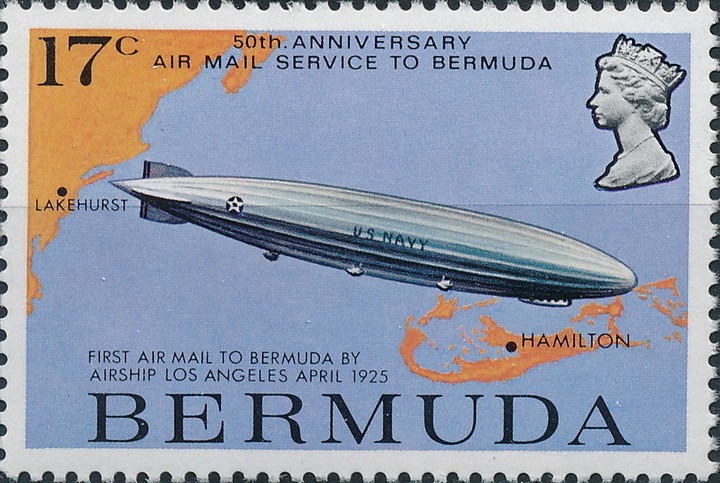

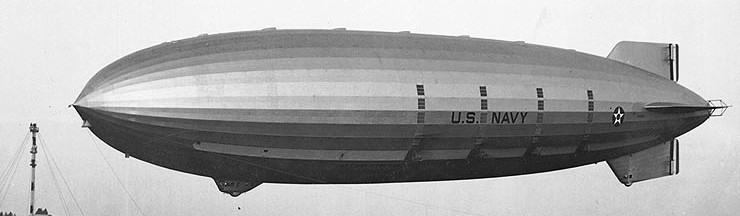

After a

safe 15-hour flight from the US Naval Air Station at Lakehurst, New Jersey,

USA, the famous United States Navy 656 foot dirigible airship the ZR-3 Los Angeles (ex LZ126) which had earlier made a unique appearance over

Washington, DC during the Presidential inauguration of President Herbert Hoover,

also made

history in Bermuda and in the process created a public sensation. In fact,

she visited the island twice in 1925. A 2.742 million cubic foot rigid airship,

she brought the very first delivery of

official "Airmail" (200 lbs or 90 kilos). The

Los Angeles was only a year old then. She was built in Friedrichshafen, Germany in

August 1924 by the Zeppelin

factory initially as LZ-126 and partially funded by Germany's war reparations

owed to the United States. She left Germany in mid-October 1924 for

delivery to the United States Navy. After a 3-day trans-Atlantic flight she

arrived at the US Naval Air Station, Lakehurst, New Jersey, where her

hydrogen-lifting gas was replaced by non-flammable helium. This greatly

increased her safety but also significantly reduced her payload and range. In

late November 1924 she was commissioned as the USS Los Angeles and began several

years of flight activity to explore her potential for Naval and commercial use.

Between February and May 1925 she flew twice to Bermuda and once to Puerto Rico.

On her first Bermuda visit, a storm prevented the docking of the airship. On board, guests included Rear Admiral William A.

Moffat, USN and Secretary of

the Navy , Theodore Robinson. As there was no suitable site for an airship

docking facility in Bermuda or Puerto Rico, the US Navy's oiler USS Patoka was

employed to moor her in both islands, with a mooring tower

on its stern. As a result, she could not land in Bermuda, instead dropped her cargo from the

sky. On her first visit, one bag of mail descended from her, over the grounds of

Government House, much to the amazement and delight of onlookers a safe distance

away. She then dropped two further mailbags not far from the home of the

Colonial Postmaster. The uniquely franked envelopes carried on the Los Angeles voyages are

much-prized by collectors. Sadly, in 1939 she was decommissioned and broken up

for scrap. Each round trip

from the New Jersey base to Bermuda took about 30 hours.

After a

safe 15-hour flight from the US Naval Air Station at Lakehurst, New Jersey,

USA, the famous United States Navy 656 foot dirigible airship the ZR-3 Los Angeles (ex LZ126) which had earlier made a unique appearance over

Washington, DC during the Presidential inauguration of President Herbert Hoover,

also made

history in Bermuda and in the process created a public sensation. In fact,

she visited the island twice in 1925. A 2.742 million cubic foot rigid airship,

she brought the very first delivery of

official "Airmail" (200 lbs or 90 kilos). The

Los Angeles was only a year old then. She was built in Friedrichshafen, Germany in

August 1924 by the Zeppelin

factory initially as LZ-126 and partially funded by Germany's war reparations

owed to the United States. She left Germany in mid-October 1924 for

delivery to the United States Navy. After a 3-day trans-Atlantic flight she

arrived at the US Naval Air Station, Lakehurst, New Jersey, where her

hydrogen-lifting gas was replaced by non-flammable helium. This greatly

increased her safety but also significantly reduced her payload and range. In

late November 1924 she was commissioned as the USS Los Angeles and began several

years of flight activity to explore her potential for Naval and commercial use.

Between February and May 1925 she flew twice to Bermuda and once to Puerto Rico.

On her first Bermuda visit, a storm prevented the docking of the airship. On board, guests included Rear Admiral William A.

Moffat, USN and Secretary of

the Navy , Theodore Robinson. As there was no suitable site for an airship

docking facility in Bermuda or Puerto Rico, the US Navy's oiler USS Patoka was

employed to moor her in both islands, with a mooring tower

on its stern. As a result, she could not land in Bermuda, instead dropped her cargo from the

sky. On her first visit, one bag of mail descended from her, over the grounds of

Government House, much to the amazement and delight of onlookers a safe distance

away. She then dropped two further mailbags not far from the home of the

Colonial Postmaster. The uniquely franked envelopes carried on the Los Angeles voyages are

much-prized by collectors. Sadly, in 1939 she was decommissioned and broken up

for scrap. Each round trip

from the New Jersey base to Bermuda took about 30 hours.

Her two later sister-ships the "Graf Zeppelin" and "Hindenburg" were destined to make history of their own across the Atlantic and over Bermuda before the next decade finished.

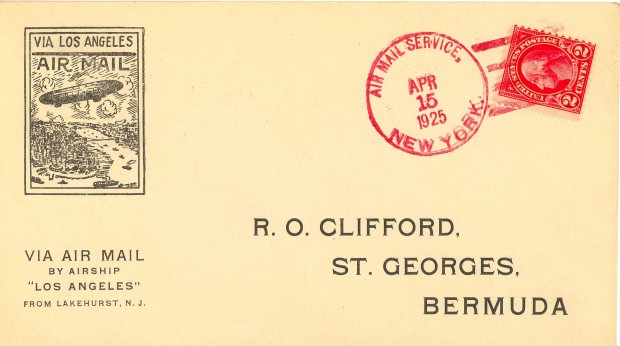

![]()

On this occasion, the docking in Bermuda with the USS Patoka was smooth with no storm and 100% successful. This time, not just one but three mailbags containing 2,341 - some accounts say 3,000 - items were dropped, close to the home of Bermuda's Colonial Postmaster. Incoming airmail was delivered and outgoing airmail was collected stamping, franking and delivery to via Lakehurst to New York.

![]()

This 776-foot blimp was flying from Friedrichshafen in Germany to Lakehurst, New Jersey, also as war reparations to the USA. This was her first transatlantic flight, having made her maiden flight less than a month earlier. Her visit was unexpected, due solely to a potentially hazardous squall to the west of Bermuda. She did not stop, but passed directly over St. George's, much to the amazement of town residents. She dropped a packet of postcards, intended for delivery first to the town's post office and from there to New York, after a tear in the fabric of her top fin was repaired. Initially, this bag of airmail was feared lost. But a St. George's boatman retrieved the bag from the sea. The St. George's Post Office Postmaster, after seeing how the sea had soaked off the stamps of the postcards, dried them and applied a St. George's date stamp of October 15, 1928 as well as the "Air Mail Service Bermuda" hand stamp used three years earlier when the Los Angeles had visited Bermuda.

![]()

Captain W. N. Lancaster attempted to fly from Long Island, USA, to Bermuda in the Curtiss Flying Fish Ireland class seaplane, as part of an attempt on the London to Cape Town speed record for the Putnam Expedition. He was accompanied by Lieutenant H. W. Lyon and sponsor G. P. Putnam. He was not successful. The team tried again, this time from Hampton Roads, Virginia, again with no luck. Unconfirmed reports said the plane sank 185 miles from Bermuda.

![]()

![]()

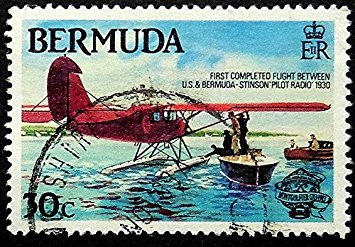

Three Americans began their own version of the Great American Dream - and

caused a great Bermuda one. Captain Lewis Alonzo Yancey, William H. Alexander and Zeh

Bouck were determined to carve out their own unique niche in aviation history by being the

first to make the then-hazardous journey by air from the North American mainland.

Their plane was a customized Stinson SM-1FS

"Detroiter" monoplane mounted on a pair of EDO floats, powered by a single 300

horsepower Wright Whirlwind motor, completely without navigational aids except a compass

and a single US Navy survey map. The plane had a top speed of 118 miles per hour, a

cruising speed of 100 miles an hour and a standard cruising range of 550 miles which left

no margin of error.

Three Americans began their own version of the Great American Dream - and

caused a great Bermuda one. Captain Lewis Alonzo Yancey, William H. Alexander and Zeh

Bouck were determined to carve out their own unique niche in aviation history by being the

first to make the then-hazardous journey by air from the North American mainland.

Their plane was a customized Stinson SM-1FS

"Detroiter" monoplane mounted on a pair of EDO floats, powered by a single 300

horsepower Wright Whirlwind motor, completely without navigational aids except a compass

and a single US Navy survey map. The plane had a top speed of 118 miles per hour, a

cruising speed of 100 miles an hour and a standard cruising range of 550 miles which left

no margin of error.

With Yancey navigating, Alexander piloting and Bouck operating his primitive, portable on-board radio equipment, the trio of intrepid aviators launched themselves and their flying machine, which they named Pilot Radio, into the skies above New York State and headed east, hoping to make a non-stop flight to Bermuda and a pinpoint landing in Bermuda - an impossible ambition with their lack of radio-direction-finding equipment and the fact that such RDF equipment capable of sending a guiding beam to an aircraft in flight was not to be introduced into Bermuda until six years later.

Nevertheless, clad in their heavy leather flying suits and goggles, they gunned their frail craft over the Atlantic - and prayed that their fates would indeed lead them to Bermuda and into fame and fortune. They were lucky. When night embraced the Atlantic ocean and sky in a curtain so thickly black that they could not even see the stars to use basic celestial navigational principles they were lost, their map and compass useless. They were also out of fuel. Their aircraft had consumed more than had been estimated, as its propeller had bitten into the winds and salt spray of the Atlantic air-currents.

They had no option but to land on

water, to wait out the long hours of dark. Somehow, their plane floated, instead of

sinking. Their hopes had not been entirely dashed. They knew they were somewhere in the

vicinity of Bermuda. With the wireless equipment provided by the radio magazine that had

sponsored them, which resulted in the plane being named Pilot Radio, they sent their

call-sign '2XBQ' repeatedly into the night ether.

They had no option but to land on

water, to wait out the long hours of dark. Somehow, their plane floated, instead of

sinking. Their hopes had not been entirely dashed. They knew they were somewhere in the

vicinity of Bermuda. With the wireless equipment provided by the radio magazine that had

sponsored them, which resulted in the plane being named Pilot Radio, they sent their

call-sign '2XBQ' repeatedly into the night ether.

Little did Yancy, Alexander and Bouck know at the time that they were not the only ones to incur a sleepless, worried night. In Bermuda, the staff at the St. George's Cable & Wireless Station had also been up all night, transmitting on the 600 meters wavelength, trying to contact the plane. In the very early half-light hours of April 2, the by then very weak '2XBQ' signal transmitted from the plane on batteries that had nearly run down, was heard by Wireless Station operators in Bermuda. Using their more powerful set, they gave Morse-code directions to the downed aviators. They also put out a call to the West India Oil Company at St. George's, which supplied a boat and crew to take out and pump a fresh supply of fuel for the aircraft of the intrepid aviators. And it was from the Wireless Station that the authorities and general public of Bermuda were first informed of a drama at sea, with Captain Yancey and his crew having announced their incredible intention of trying to take off again from the Atlantic, to resume their epoch-making flight to Bermuda. Their dream of making the first-ever direct flight from North America to Bermuda was still intact, even if it had been dented a little with a nightfall touchdown on the Atlantic Ocean surface.

Later that day, Yancey, Alexander and Bouck successfully took off from the ocean and sighted Bermuda. They made a triumphant landing at 10 am in Hamilton Harbor. When they set foot on dry land, they were mobbed by ecstatic Bermudians - and hailed as trailblazers. Among the greeters was a Miss Kathleen Jones who presented Easter lilies to the crew of the plane. In the celebrations that followed, which included several fly-pasts of "Pilot Radio" around Bermuda, they were presented with $1,000 apiece ($1,500 from the Trade Development Board, $1,000 from the Hotel Men's Association and $500 from the Bermuda Poll Committee).

Bermudians saw in that unique flight a vision of things to come - of aircraft that would one day leave the USA loaded with US tourists, bound for a holiday in our beautiful Islands. But Captain Yancey and his crew uttered words of caution to temper the jubilation. He prophesied that regular service by airplane would commence to Bermuda only when aircraft and Bermuda were equipped with proper RDF equipment to aid pilots and navigators. He also decided that it would tempt fate too much to attempt to fly back to the US mainland from Bermuda in Pilot Radio. So he, Alexander and Bouck dismantled and crated it for departure on the MS Bermuda - and left on that ship, for a slower but safer voyage by sea back to their homeland. However, they did leave one part of their historic aircraft behind them. They presented the Bermuda Historical Society with its gyro compass. Unfortunately, no one knows what happened to the historic instrument. Searches have found that it is no longer in the Society's hands. It may have been misplaced or stolen years ago.

![]()

With Bermuda's earlier first aircraft arrival milestone still capturing media attention from three months earlier, Roger Q. Williams, barnstormer, stunt and test pilot, with Canadian World War I veteran Captain J. Errol Boyd as co-pilot and Lieutenant Harry P. Connor, a U.S. Navy-trained navigator, arranged to fly Miss Columbia, a Wright-Bellanca WB-2 single-engine monoplane with wheels, on a nonstop, round-trip flight to Bermuda from Long Island. Miss Columbia had already achieved fame as the plane flown by Clarence D. Chamberlin and Bert Acosta when they set a world’s endurance record of more than 51 hours in May 1927. Chamberlin and Charles A. Levine then flew it nonstop 3,910 miles the following month to Eisleben, Germany. The announced purpose of a round-trip Bermuda flight without landing, according to Williams, was to ascertain if, with the navigation equipment then available, a regular airline service could be established between New York and Bermuda. He said that if a small, single-engine plane such as Miss Columbia could make the round trip and find the island with ordinary navigational methods, scheduled passenger flights to the island would be easily achievable with radio-equipped amphibian planes powered by two or more engines. The Miss Columbia trio departed from Roosevelt Field on Long Island early in the morning that day, in clear weather. Connor had no problems with the navigation, but since there was no radio on board, he was unable to report their progress as Bouck had done three months earlier on Pilot Radio. The skies gradually darkened as they flew on, and as they approached Bermuda shortly after noon they ran into a driving tropical storm. ‘Within forty miles of the island, we struck one of the fiercest rain squalls I have ever flown through,’ Williams said in a New York Times interview after the flight. ‘We went down to 200 feet and came in over the city [Hamilton] and circled. It looked like a landing [was inevitable] on a field I couldn’t see, for that water got to the magneto and the engine began to kick up. We circled for twenty minutes, hoping for a place to land or a let-up in the rain, but neither showed up. It looked like a crash to me. Finally, we turned seaward again because there was nothing else to do. A few miles out the rain stopped, the sky cleared and the old motor started doing its old stuff again, so we came home. What pleases me is we struck those little chunks of land, scattered over only eighteen miles of the Atlantic Ocean, right on the nose, without any radio bearings." What Williams did not mention was that they had dropped a bag of mail on the Belmont Manor Golf Club grounds, to the rear of the Hotel Bermuda. When a reporter asked him about landing there, Williams said the golf course was the only possible stretch of land where a landing might have been possible, but that a crackup was ‘certainly a possibility.’ The return flight to New York was uneventful. They made a night landing at Curtiss Field instead of Roosevelt Field because of thick haze over their departure airport. The elapsed time for the 1,560-mile flight was 17 hours 8 minutes, and they had enough fuel remaining to fly another 1,000 miles. (The trip served as a practice run in the same Bellanca for a transatlantic flight by Boyd and Connor from Newfoundland to England the following October). The successful round-trip flight to Bermuda had an unpleasant brief aftermath for Williams. The Bermudian government sent a protest to the U.S. State Department because the fliers had not notified the island’s authorities about their plans and had not received permission beforehand. Williams’ pilot license was suspended by the Aeronautics Branch of the Department of Commerce for several weeks as a result.

![]()

With Mrs. Beryl Gwyn Hart of Ohio and Lieutenant William S. McLaren of the US Naval Reserve aboard, the white painted Bellanca CH300 Pacemaker high wing seaplane Tradewind landed safely in Bermuda from Hampton Roads, Virginia. It was a perfect landing in Hamilton Harbour after an 8-hour flight. It was much-celebrated in Bermuda as the first completed flight between the U.S. and Bermuda, and the first leg of a projected trans-Atlantic, New York-Bermuda-Azores-Paris flight designed to demonstrate the commercial possibilities of trans-Atlantic flying.

![]()

But after just under three days in Bermuda, the plane and by-then-famous couple, after partying galore in Bermuda, took off on January 10, 1931, from Hamilton Harbour to the Azores and then disappeared into a huge black cloud. Neither the occupants or aircraft were never heard from again. Mrs Hart was a contemporary of Amelia Earhart and almost as well known as the latter. The Bellanca CH-300 Pacemaker was a six-seat utility aircraft built primarily in the United States in the 1920s and 1930s. It was a development of the Bellanca CH-200 fitted with a more powerful engine and, like the CH-200, soon became renowned for its long-distance endurance, so much so that a 400 was later successfully introduced.

![]()

Pilot C. Nelmes of Bermuda,

a local aviation piuoneer, was killed when his aircraft an Ely- Curtiss HS-2L aircraft,

of pre-World War 1 vintage, of the type once used by the

United States Navy and Canadian authorities but later deemed by the former to be

too dangerous to fly after 1928, crashed at Grassy Bay off HM Dockyard when

over-flying a ship. There were two survivors. It is believed that Nelmes

bought his Curtiss HS-2L

in Canada, from OPAS. This aircraft is believed to have been one of the first

aircraft registered in Bermuda. This flying boat made

its debut as a warplane by patrolling against enemy submarines. The manufacturer

was Curtiss Aeroplane and Motor Co. Inc. of Hammondsport and Buffalo, NY, and

the patrol flying boat was built under license by Galaudett Flying Boat Company,

College Point, Long Island, NY. Its wingspan was just over 74 feet; height 14'

7"; length 38' 6"; top speed 91 mph; range 517 miles; empty weight

4,700 lbs; gross weight 6,432 lbs; fuel capacity was 141 gallons; crew were

three people; service ceiling was 5,000 feet; engine was a Liberty 12 at 350 HP

and the sea level climb was 220 feet per minute.

Pilot C. Nelmes of Bermuda,

a local aviation piuoneer, was killed when his aircraft an Ely- Curtiss HS-2L aircraft,

of pre-World War 1 vintage, of the type once used by the

United States Navy and Canadian authorities but later deemed by the former to be

too dangerous to fly after 1928, crashed at Grassy Bay off HM Dockyard when

over-flying a ship. There were two survivors. It is believed that Nelmes

bought his Curtiss HS-2L

in Canada, from OPAS. This aircraft is believed to have been one of the first

aircraft registered in Bermuda. This flying boat made

its debut as a warplane by patrolling against enemy submarines. The manufacturer

was Curtiss Aeroplane and Motor Co. Inc. of Hammondsport and Buffalo, NY, and

the patrol flying boat was built under license by Galaudett Flying Boat Company,

College Point, Long Island, NY. Its wingspan was just over 74 feet; height 14'

7"; length 38' 6"; top speed 91 mph; range 517 miles; empty weight

4,700 lbs; gross weight 6,432 lbs; fuel capacity was 141 gallons; crew were

three people; service ceiling was 5,000 feet; engine was a Liberty 12 at 350 HP

and the sea level climb was 220 feet per minute.

The United States Navy flew them on anti-submarine duty off the East Coast from bases in Nova Scotia. When WW1 was over, they donated twelve of the planes to Canada. In 1919, the first HS-2Ls went into Canadian civil use in Québec forestry work, remaining the predominant bush aircraft until 1926 or 1927. It was to mark the dawn of the Canadian bush pilot tradition. The Ontario Provincial Air Service (OPAS) was formed by the Government of Ontario in 1924 to protect the province's vast forests. At the time it was one of the largest airborne forest services in the world. They constructed a hangar at the edge of the St Mary's River in Sault Ste. Marie to house their fleet of surplus Curtiss HS-2L's. Using aerial detection of forest fires, aerial transportation of fire crews and equipment, map making, aerial photography, and forest inventory, they ushered in a new era of ecological maintenance -- in their first year of operation alone, 600 forest fires were spotted. The wooden hull of the flying boat presented a few disadvantages. It could be damaged by rocks or dead trees, and had a tendency to get waterlogged after the long weeks and even months it spent in water. This increased the weight of the craft and caused performance to become sluggish. The aircraft needed to land in a fairly large lake to be able to take off again. It often required a mile to take off and climbed so slowly that it needed a lake or sea surface of 3 to 5 miles in length to achieve sufficient height to clear trees and hills. Its average speed was about 65 miles per hour (105 km/hr). The H-boat, as it was known, had an ambiguous safety record - it could land in rough water, but if it stalled and went into a spin, it was impossible to pull it out again. The U.S. Navy branded it as too dangerous for violent maneuvers, and afterward there were few accidents - as one USN officer said: "All the good HS-2L pilots were killed off by 1923, and therefore there were no more accidents."

![]()

She was searching for the missing yacht Curlew. It was not a success but considered a valuable operational exercise. She moored in the Great Sound and hundreds of Bermudians were fascinated.

![]()

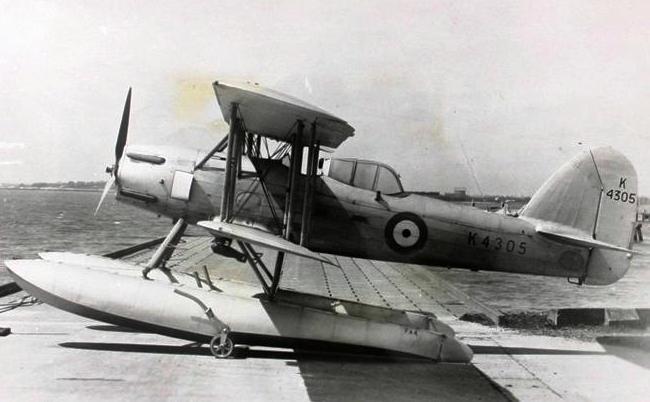

A hanger was constructed at the Royal Navy Dockyard in Sandys Parish and the small RAF Bermuda station began. Although controlled by the Royal Navy, the base was manned entirely by Royal Air Force personnel. But all British aircraft were all part of the Fleet Air Arm (FAA), which took over from the pre-1920s Royal Naval Air Force. They included a number of Hawker Osprey, Fairey Seafox and Supermarine Walrus seaplanes, catapult-launched from Royal Navy warships based in Bermuda at the Dockyard.

![]()

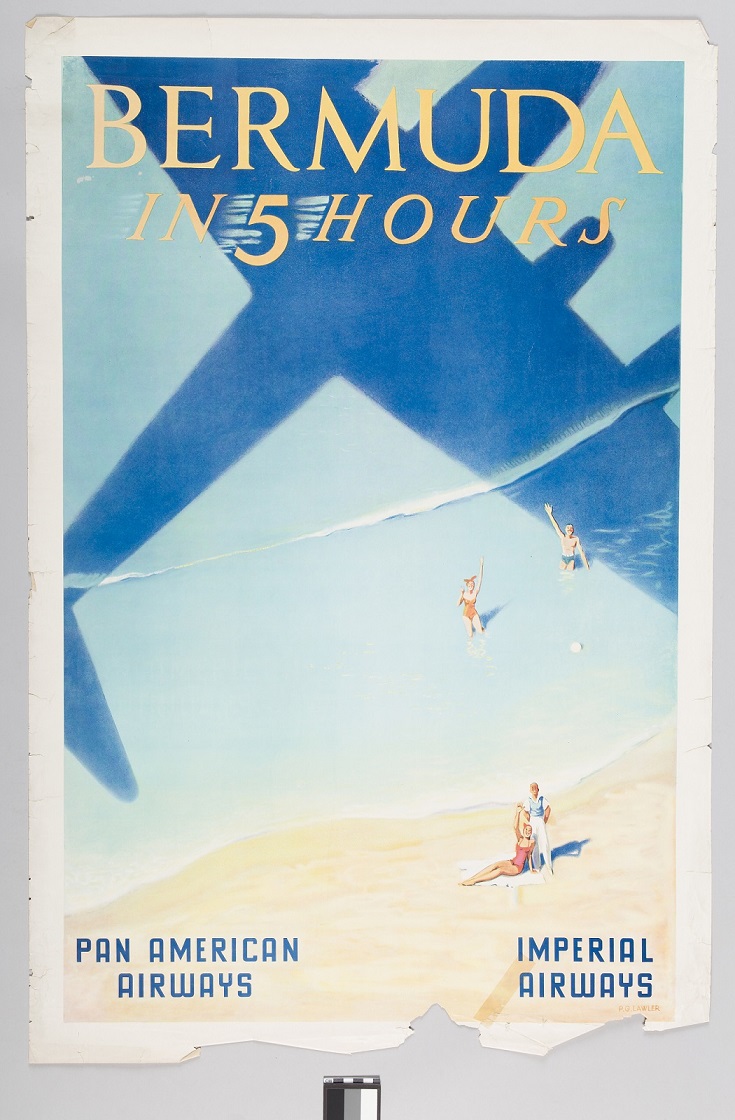

A direct result of Juan Trippe's

initiatives in creating Pan American World Airways, Darrell's

Island in Bermuda's Great Sound, once an internment camp for Boer War prisoners, was

selected as Bermuda's first seaplane airport. His

Pan American World Airways was ready to chart new Atlantic routes. He wanted the New York

to Bermuda and a Bermuda to Europe run, via the Azores. But he had problems acquiring

landing rights in the Azores and in Newfoundland, to link to his proposed Bermuda service.

Nor could he resolve the problem of

navigating over the Atlantic without radio direction finding. Frustrated, he turned to the

Far East, where there was less bureaucracy over landing rights, an easier navigational

system of staging posts - and the lure of Hawaii, Pacific islands and Philippines, on the

route to China.

A direct result of Juan Trippe's

initiatives in creating Pan American World Airways, Darrell's

Island in Bermuda's Great Sound, once an internment camp for Boer War prisoners, was

selected as Bermuda's first seaplane airport. His

Pan American World Airways was ready to chart new Atlantic routes. He wanted the New York

to Bermuda and a Bermuda to Europe run, via the Azores. But he had problems acquiring

landing rights in the Azores and in Newfoundland, to link to his proposed Bermuda service.

Nor could he resolve the problem of

navigating over the Atlantic without radio direction finding. Frustrated, he turned to the

Far East, where there was less bureaucracy over landing rights, an easier navigational

system of staging posts - and the lure of Hawaii, Pacific islands and Philippines, on the

route to China.

Juan Trippe had seen for himself, in visits by sea to Bermuda, how the British Furness Withy organization, to attract tourists on its New York to Bermuda ships, had built new hotels in Bermuda. He borrowed the idea for the Pacific and began construction of a chain of Bermuda style hotels for his many Pan American staging posts on the China Clipper route. Thus he started some unique tourism history of his own that Bermuda was later to copy (local records claim, inaccurately, that Bermuda was the forerunner of tourism). His flying boats scored outstanding successes because of their ability to fly long distances or to carry large payloads over short distances, and because the cost of constructing terminal facilities was appreciably lower than on land. Also, they had a better chance of surviving a forced landing on water. So they flourished at a time when, by and large, land based aircraft were not available with comparable payload and range performance. No commercial airline today would operate a four engine aircraft without stopping, across the Atlantic or Pacific with a payload of only 20 passengers, but Pan American World Airways did so very successfully then.

![]()

In 1935 in Ottawa,

Canada, British civil aviation interests matched Trippe's initiatives. United Kingdom and

other major British Empire nations wanted air services to connect the Empire for joint

defence and better trade relations. They authorized service between Canada and Britain, a

Canadian transcontinental system, New York to Bermuda and further trans Atlantic flights

by British and American aircraft. It was the dawn of a new era for Bermuda. From the meeting in Ottawa came the

plans that made possible the firm idea of the creation of regular flying boat flights

between New York and Bermuda and points east by Imperial Airways and Pan American World

Airways - and the establishment of Trans Canada Air Lines, later Air Canada. The intention was to create for the

passenger traffic and mail conveyancing of the British Empire a carbon copy of what had

occurred in the United States. There, a network of small domestic air companies had been

knitted together to form a sophisticated air transport system. It included Western Air

Lines, United Air Lines, Eastern Air Lines and Northwest Air Lines.

In 1935 in Ottawa,

Canada, British civil aviation interests matched Trippe's initiatives. United Kingdom and

other major British Empire nations wanted air services to connect the Empire for joint

defence and better trade relations. They authorized service between Canada and Britain, a

Canadian transcontinental system, New York to Bermuda and further trans Atlantic flights

by British and American aircraft. It was the dawn of a new era for Bermuda. From the meeting in Ottawa came the

plans that made possible the firm idea of the creation of regular flying boat flights

between New York and Bermuda and points east by Imperial Airways and Pan American World

Airways - and the establishment of Trans Canada Air Lines, later Air Canada. The intention was to create for the

passenger traffic and mail conveyancing of the British Empire a carbon copy of what had

occurred in the United States. There, a network of small domestic air companies had been

knitted together to form a sophisticated air transport system. It included Western Air

Lines, United Air Lines, Eastern Air Lines and Northwest Air Lines.

The American air industry had commenced development of a fleet of new land airplanes, such as the Boeing 247 transport in 1933, the Douglas DC-1 and DC-2 and the first DC-3s. American carriers with their new planes were capable of snatching the bulk of traffic away from British interests, unless the British aircraft industry became aggressive. The problem was particularly acute in Canada, where tentacles of American carriers had penetrated significantly into Canadian cities close to the American border; and elsewhere, given the domination that Juan Trippe's Pan American World Airways had established with its overseas and over-water routes with Sikorksy flying boats.

Imperial Airways needed aircraft of similar caliber, not only to fly the Atlantic but also to meet its obligations in India and Australia imposed on it by the Imperial Government's Empire Air Mail scheme. With the huge bulk of mail this involved, Imperial Airways invited tenders from prominent aircraft manufacturers in Britain. Only one responded - Short Brothers - with the proposal for its Short Empire 'C' class flying boat. With no other options to pursue, Imperial accepted. Seldom in the history of commercial aviation was such a gamble taken on an untried and untested aircraft. Never in the field of human history since has such a gamble paid such handsome dividends. There was no time for normal extensive prototype development of the type that commercial aviation today requires and regulatory agencies demand. Forty-two Short Empire 'C' class British flying boats began coming off the production lines, at the rate of two a month - and were put into immediate service by Imperial Airways to India and Australia.

![]()

The late A. W. "Bill" Forbes, wireless engineer

This gentleman (who died when he was nearly 97 on August 31, 1996) first arrived in Bermuda by ship from Britain. He led a team of specialists from Cable & Wireless who began to pioneer in Bermuda for the Imperial Government a superior system and station for Air to Ground radio-direction finding for ships. In 1937, he led the team in both Air to Ground and Ship-to-Shore point-to point radio direction finding and telegraph services for aircraft. When, on May 6, 1936 the German Zeppelin Transport Company began its Hindenburg air ship from Berlin, Bermuda's Cable and Wireless station, particularly including Mr. Forbes, had day and night activity. Via radio telephone, its 36 staff guided aircraft, dirigibles and ships across the Atlantic. This was done with bearings, messages, weather conditions and more. They worked shifts around the clock, in a constant atmosphere of clicking machines, hum and distinctive odor of electrical equipment, signal buzzes and voices calling from the air and sea via loudspeakers. They handled often chronic daily emergencies at sea or in the air near or far beyond Bermuda. They had to breakfast, lunch or dine on eggs, bacon and toast cooked up on a hot plate at work for many days at a time, with makeshift meals interrupted by emergencies.

![]()

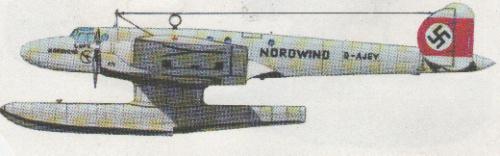

Germany's

efforts in the North Atlantic attracted huge interest. The program was

administered by Freiherr von Buddenbrock who was Atlantic Air Transport Director

of Deutsche Luft Hansa. He went to the USA on the first flight and returned on

the last. When Luft Hansa -

Lufthansa - founded in 1926 began in services from Germany to Brazil in 1936, it used five

models of the Dornier Do 18 on its service from Berlin to Lisbon to the

Azores to Bermuda to New York, USA, periodically when weather conditions

required, also from New York to Sydney, Nova Scotia, from there to the Azores

and Lisbon. They were improvements on the

Dornier Wal (Whale) flying boats. The only snag was that they could not use

Ireland - the Irish had barred them from using Galway Bay, the only suitable

place in Ireland. The crews of the two flying boats Aeolus (see

left photo, in Bermuda) and Zephyr that visited Bermuda included

Flugkapitans Blankenburg, von Engel, Graf Schack, Mayr, von Captain Baron F. W.

Buddenbrock and Direktor Freiherr von Gablenz; wireless operators Stein and

Ehlberg; flying engineer Gruschwitz and engineer Eger. The flying boats had an

astonishingly good safely record. Except for a leaking radiator on the first

departure there was no trouble of any sort and no replacements in either the

flying boats or their Junkers Jumo heavy-oil motors. Lufthansa stationed the depot

(catapult) ship Schwabenland (a

converted cargo ship) west of the Azores.

The most famous of

the aircraft of the Ha

139 was the Nordwind - shown here - in Deutsche Luft Hansa livery of about

1938.

Germany's

efforts in the North Atlantic attracted huge interest. The program was

administered by Freiherr von Buddenbrock who was Atlantic Air Transport Director

of Deutsche Luft Hansa. He went to the USA on the first flight and returned on

the last. When Luft Hansa -

Lufthansa - founded in 1926 began in services from Germany to Brazil in 1936, it used five

models of the Dornier Do 18 on its service from Berlin to Lisbon to the

Azores to Bermuda to New York, USA, periodically when weather conditions

required, also from New York to Sydney, Nova Scotia, from there to the Azores

and Lisbon. They were improvements on the

Dornier Wal (Whale) flying boats. The only snag was that they could not use

Ireland - the Irish had barred them from using Galway Bay, the only suitable

place in Ireland. The crews of the two flying boats Aeolus (see

left photo, in Bermuda) and Zephyr that visited Bermuda included

Flugkapitans Blankenburg, von Engel, Graf Schack, Mayr, von Captain Baron F. W.

Buddenbrock and Direktor Freiherr von Gablenz; wireless operators Stein and

Ehlberg; flying engineer Gruschwitz and engineer Eger. The flying boats had an

astonishingly good safely record. Except for a leaking radiator on the first

departure there was no trouble of any sort and no replacements in either the

flying boats or their Junkers Jumo heavy-oil motors. Lufthansa stationed the depot

(catapult) ship Schwabenland (a

converted cargo ship) west of the Azores.

The most famous of

the aircraft of the Ha

139 was the Nordwind - shown here - in Deutsche Luft Hansa livery of about

1938.

On September 11, 1936 the

aircraft began arriving in Bermuda, complete with their Nazi insignia. The first arrival

was Captain Baron F. W. von Buddenbrock. There were four more visits to Bermuda by various German float

planes including several by the Ha 139 made by Boem und Voss of both aircraft and

battleship fame. They flew into Bermuda to get more fuel. They landed in Hamilton Harbor. Engines were four

600 hp Junkers Jumo

205C 12-cylinder diesels. Span was 88 feet 7 inches (27m). Length was 63 feet 11.75

inches (19.5 meters). Wing area was 1,259.38 square feet (117 square

meters). Catapult take off weights were 38,581 pounds (17,500 kilograms).

Maximum speed

was 196 miles per hour (315 kilometers per hour) at sea level. Operational ceiling was

11,480 feet (3,500 meters). Maximum range was 3,395 miles (5,300 kilometers).

They continued until the war ( 1939 to 1945). Unlike the flying boats it

serviced which were trouble-free, the crew of the Shabenland had an arduous

time. No other catapult ship could be spared for the German North Atlantic

experiments so the Schwabenland had to steam across the Atlantic after each

double-launch in order to start the flying boats on their next trips. In each

case, the aircraft landed alongside and were then

winched up or down for fuel or repair, or caterpult take-off from the ship,

as the larger photos below show.

On September 11, 1936 the

aircraft began arriving in Bermuda, complete with their Nazi insignia. The first arrival

was Captain Baron F. W. von Buddenbrock. There were four more visits to Bermuda by various German float

planes including several by the Ha 139 made by Boem und Voss of both aircraft and

battleship fame. They flew into Bermuda to get more fuel. They landed in Hamilton Harbor. Engines were four

600 hp Junkers Jumo

205C 12-cylinder diesels. Span was 88 feet 7 inches (27m). Length was 63 feet 11.75

inches (19.5 meters). Wing area was 1,259.38 square feet (117 square

meters). Catapult take off weights were 38,581 pounds (17,500 kilograms).

Maximum speed

was 196 miles per hour (315 kilometers per hour) at sea level. Operational ceiling was

11,480 feet (3,500 meters). Maximum range was 3,395 miles (5,300 kilometers).

They continued until the war ( 1939 to 1945). Unlike the flying boats it

serviced which were trouble-free, the crew of the Shabenland had an arduous

time. No other catapult ship could be spared for the German North Atlantic

experiments so the Schwabenland had to steam across the Atlantic after each

double-launch in order to start the flying boats on their next trips. In each

case, the aircraft landed alongside and were then

winched up or down for fuel or repair, or caterpult take-off from the ship,

as the larger photos below show.

Lufthansa in Bermuda, 1936. All five above original photos were taken by the late "Bill" Forbes in Bermuda. Copyright by one of his sons this author, Keith Forbes. Provided here with permission exclusively and solely for this unique History of Aviation in Bermuda website.

![]()

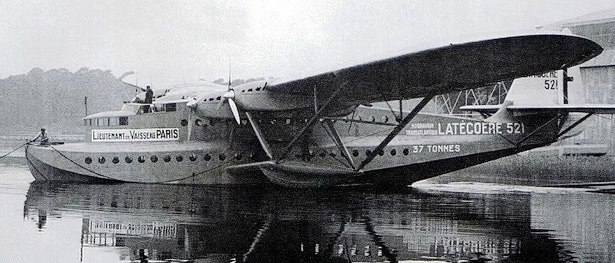

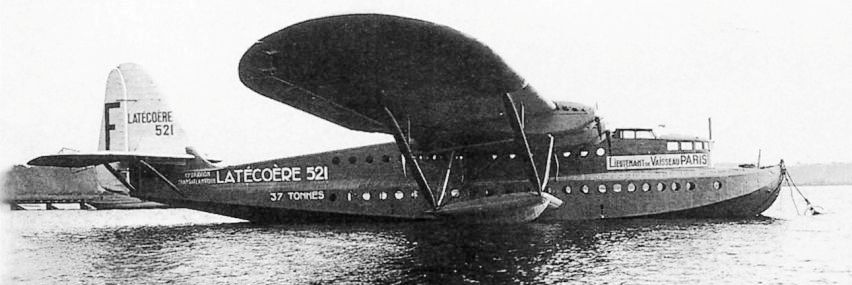

Photo courtesy Latecoere archives 1995

Air France - Transatlantique's - later, Air France - Latecoere 521 F-NORD "Lieutenant de Vaisseau Paris" made 2 visits to Bermuda when flying from Paris on surveys. Here, she is seen at the brand-new Bermuda airport on Darrell's Island. Air France omits any mention of this in its own archives.

![]()

On that day, Bill Forbes boarded the Royal Navy warship HMS Dragon at HM Dockyard in Bermuda. She left port next day to circumnavigate Bermuda completely, for a very special purpose. As a radio direction finding engineer, Forbes's task for the Imperial Government was to calculate and log radio direction finding calibrations by sea for ships and aircraft approaching Bermuda, having already done so by land radio direction finding. This very successful special project removed from Bermuda all remaining navigational obstacles for ships and flying boats at sea to find Bermuda and safely navigate its dangerous and extensive ring of outer coral reefs. From February 20, Forbes and his team followed this up by beginning and finishing their design, at Bermuda's highest point, The Peak in Smith's Parish, of what became the Eagle's Nest - the world's first Adcock short wave radio direction finding station, specifically for pilots and navigators of Imperial Airways and Pan American World Airways flying boats and other aircraft to home in to the signal. It was another 'first' for Bermuda in aviation support technology.

These initiatives established the navigational systems that were used in all weather conditions to safely guide ships and flying boats right into Bermuda. They made Bermuda attractive to Imperial Airways and Pan American. They put Bermuda firmly for the first time into mainstream winter and summer tourism for visitors by air from around the globe.

![]()

The German dirigible was promoted as the future of trans-Atlantic flight, but instead it became the notorious poster child of air disasters. As the hydrogen-filled blimp was landing in Lakehurst, it suddenly burst into flames and crashed in front of shocked bystanders, killing 35 of the 100 passengers and crew on board - and putting an end to the short-lived air travel program. The airship had crossed the Atlantic safely twenty times before but it became the effective end of airship technology having the edge over winged aircraft. One result of this was the decision of Imperial Airways and Pan American World Airways to put forward their plans to fly a shorter distance over the Atlantic, specifically to Bermuda.

Hindenburg air disaster

![]()

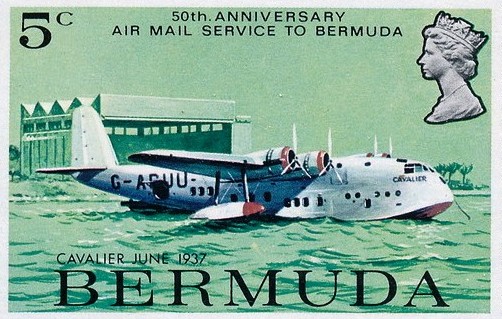

Thus was the scene set for Imperial Airways (see http://www.britishairways.com/travel/explore-our-past/) and Pan American World Airways to establish their flying boat services between New York and Bermuda. Bill Forbes and his team readied their radio direction finding equipment, working through the night. On Darrell's Island, a team worked to re-assemble and then check the Imperial Airways' Short Empire C-class RMA Cavalier flying-boat G-ADUU, shipped in parts from England, under the supervision of Imperial's Chief Engineer Len Turnhill, working with Imperial Airways and Bermudian staff.

The next day, the flying boat started engines, cruised on pontoons through Hamilton Harbor and soared into mid Atlantic airspace for its first Western Hemisphere flight, to test and calibrate its on board radio equipment and match its signals with those transmitted by Forbes and his team on the Adcock short wave radio direction finding equipment. Then came May 25, 1937. It was a proud day for Bermuda. The Imperial Airways' Short Empire C class flying boat RMA Cavalier took off from the unofficially opened and not quite finished Darrell's Island Marine Air Terminal, for New York. She was commanded by Capt. Neville Cumming, with co-pilot First Officer Neil Richardson, radio engineer Patrick Chapman, and steward Robert Spence.

At the same time, the Pan American Airways' Sikorsky S-42, NC 16735, by then renamed by Mrs. Trippe as Bermuda Clipper, also flew from Port Washington, NY to Bermuda. She did a successful reciprocal survey of the route. (Especially noteworthy and quote worthy is the fact that this was two years before Pan Am started its New York to London service.) Bermuda Clipper was commanded by Capt. R. O. D. Sullivan. Passengers included Mr. John Barritt of John Barritt & Son Mineral Water Company; Major Neville, a staff officer at Admiralty House; Mr. E. P. T. Tucker, General Manager of John S. Darrell & Co.

Also aboard were Mr. E. R. Williams of J. E. Lightbourn & Co. ( later, Mayor of Hamilton); Mr. H. B. L. Wilkinson, of Bailey's Bay; Miss Minna Smith, a nurse at King Edward VII Memorial Hospital; Mr. Terry Mowbray, Sports Director of the Bermuda Trade Development Board. Mr. & Mrs. Richard Scott of Boston were returning from their honeymoon in Bermuda; and Mr. Eugene Kelly, Mrs. Alice James and Mrs. John Fullarton, all of New York.

Later, in support of the two airlines and expecting more communications traffic, the West India and Panama Telegraph Company Ltd - in conjunction with Britain's Imperial & International Communications - installed an internal teleprinter system between the airlines' offices and the Air to Ground station.

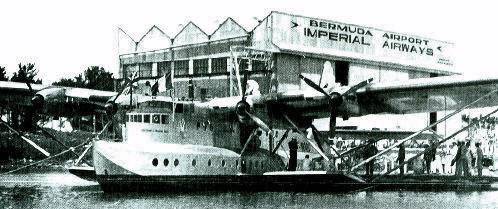

![]()

Bermuda's first seaplane port, on Darrell's Island, before which there was no such facility. Owned by the Bermuda Government, it enabled Bermuda to become known as THE mid Atlantic seaplane and flying boat airport base and resort. It was the date of the inaugural passenger and airmail flights of the Cavalier and Bermuda Clipper. Both flying boats took off from Port Washington, New York and landed safely.

Bermuda postage stamp (of later vintage) commemorated this June 1937 event

![]()

On its southerly route, its stops were at Bermuda, Azores, Lisbon, Marseilles and Southampton, England.

![]()

![]()

It was because New York weather caused problems for flying boats. At Baltimore, 30,000 people welcomed the flying boats "Bermuda Clipper and "Cavalier." Flying time to Bermuda for Bermuda Clipper, with 28 passengers, was 6 hours 25 minutes, with 5 hours 45 minutes for "Cavalier" with 17 passengers.

![]()

![]()

This Empire S-23 of Imperial Airways had become a firm favorite in Bermuda. Crashed between New York and Bermuda. Three died, ten survived after being rescued by tanker vessel "Esso Baytown." There is a plaque in tribute to the heroes and survivors at the Bermuda Anglican Cathedral.

![]()

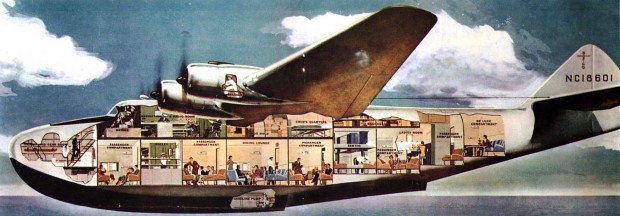

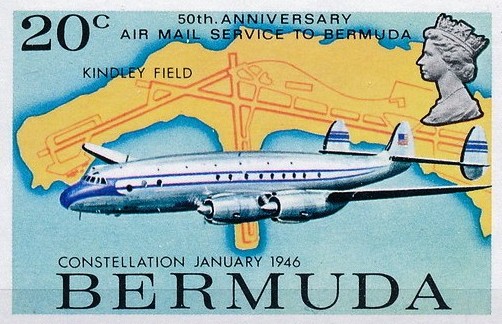

The Boeing 314

"Clipper" initially replaced the S-42 on the PA

160/161 New York service and then to the UK, Far East and Bermuda. See the book Last of the Flying Clippers. The

Boeing 314 Story. M. D. Klass. 2006. With

amenities modeled on those of the great luxury liners of the period, the 12

Boeing-314 Clippers operated by Pan Am and the three diverted to the British Overseas Airlines Corporation

under the Lend-Lease Act remain the most luxurious aircraft ever to take to the skies. The sumptuous

long-range flying boats produced by the Boeing Airplane Company, which used to fly through Bermuda in the 1930s and '40s, are

highlighted here. The lavishly illustrated book includes sections on the

aircraft's extensive use of the Darrell's Island airport in Bermuda. They were

the largest aircraft of their type ever built, with a maximum of 74 passengers

and 10 crew. They used island airports such as the one then in Bermuda as

intermediate stepping stones for ocean-spanning flights across the Atlantic and

Pacific. The aircraft were commissioned from Boeing by Pan Am founder Juan

Trippe – also the developer of Bermuda's Castle Harbour Hotel – specifically

for trans-oceanic flights. PanAm operated nine of the aircraft while three were

purchased by Imperial Airways, forerunner of today's British Airways and also

flew through Bermuda en route to New York and other destinations. The aircraft

were built between 1938 and 1941. 84,000 pounds, four-engined, they were 106

feet long, had a wing span of 152 feet and had a top speed of 199 miles per

hour. They used the massive wings of Boeing's earlier XB-15 bomber prototype to

achieve their enormous range. After World War Two, seaplanes became obsolete because new, long-range

aircraft such as the Lockheed Constellation could cross the Atlantic and Pacific

non-stop.

The Boeing 314

"Clipper" initially replaced the S-42 on the PA

160/161 New York service and then to the UK, Far East and Bermuda. See the book Last of the Flying Clippers. The

Boeing 314 Story. M. D. Klass. 2006. With

amenities modeled on those of the great luxury liners of the period, the 12

Boeing-314 Clippers operated by Pan Am and the three diverted to the British Overseas Airlines Corporation

under the Lend-Lease Act remain the most luxurious aircraft ever to take to the skies. The sumptuous

long-range flying boats produced by the Boeing Airplane Company, which used to fly through Bermuda in the 1930s and '40s, are

highlighted here. The lavishly illustrated book includes sections on the

aircraft's extensive use of the Darrell's Island airport in Bermuda. They were

the largest aircraft of their type ever built, with a maximum of 74 passengers

and 10 crew. They used island airports such as the one then in Bermuda as

intermediate stepping stones for ocean-spanning flights across the Atlantic and

Pacific. The aircraft were commissioned from Boeing by Pan Am founder Juan

Trippe – also the developer of Bermuda's Castle Harbour Hotel – specifically

for trans-oceanic flights. PanAm operated nine of the aircraft while three were

purchased by Imperial Airways, forerunner of today's British Airways and also

flew through Bermuda en route to New York and other destinations. The aircraft

were built between 1938 and 1941. 84,000 pounds, four-engined, they were 106

feet long, had a wing span of 152 feet and had a top speed of 199 miles per

hour. They used the massive wings of Boeing's earlier XB-15 bomber prototype to

achieve their enormous range. After World War Two, seaplanes became obsolete because new, long-range

aircraft such as the Lockheed Constellation could cross the Atlantic and Pacific

non-stop.

![]()

Photo courtesy Latecoere archives 1995

They definitely arrived not just once but in May, June and August 1939, after a very successful survey flight in 1936, although these Bermuda flights are not mentioned in Air France history. They were two giant 43 ton 6-engined Air France Latecoere 521/522, aircraft of Air France-Transatlantique, the early name for Air France. They were Lieutenant de Vaisseau Paris (F-NORD), with the same name as that of the French aircraft that had visited Bermuda earlier and Ville de Saint Pierre. They were easily the largest aircraft ever seen in Bermuda up to that time. They were powered by six 671kW Hispano-Suiza 12Y37 engines and first appeared in April 1937. They were planned and were proving flights for a regular trans-Atlantic service but World War II prevented this. Both aircraftwere impressed into French Navy service on 1 September 1939. These were armed with five 7.5mm Darne machine-guns and carried up to 1,200kg of bombs. But they perished during the war.

![]()

With the

outbreak of World War 2 for Britain, more Fleet Air Arm of the Royal Navy and

Royal Air Force

(RAF) aircraft were sent to Bermuda and were based at both Darrell's Island

and Boaz Island.

With the

outbreak of World War 2 for Britain, more Fleet Air Arm of the Royal Navy and

Royal Air Force

(RAF) aircraft were sent to Bermuda and were based at both Darrell's Island

and Boaz Island.

The anomaly in the command structure referred to in 1933 was rectified when this part of the Royal Navy Dockyard was transferred to the FAA and given the name of HMS Malabar.

Losses galore of British and bought from USA military aircraft began to occur in and around Bermuda from 1941 to the end of the war.

RAF at Darrell's Island in WW2

![]()

As part of the preparations for World War 2, the increased workload at HMS Malabar caused problems due to the limited space available. With so many of the locally-based or in-transit Royal Navy warships carrying catapult-launched seaplanes such as the Hawker Osprey, Fairey Seafox and Supermarine Walrus seaplanes, the need for prompt, efficient and spacious aircraft maintenance was a high priority. Thus, the new station was built. It had two good-size hangers and launching ramps on either side of the island and they allowed continuous operation in any wind direction. With the Battle of the Atlantic over, the station was reduced to care and maintenance status in 1944. Some remnants still survive.

![]()

They included Norman Sumpter, Harold Dale, Richards (first name unknown), Squires (first name unknown), Arthur (Copper) Jenkins, Charles Nunn, Robert Oatway, Fred (Red) Adderley, David Kopec, Herbert (Chummy) Zuill, Norman Jones, John Hartley Watlington and Hugh Watlington.

![]()

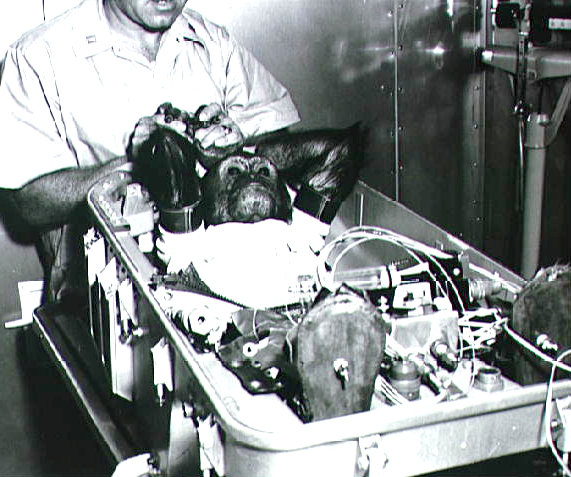

It began

with the goal of training pilots for the Royal Air Force (RAF) or the Royal

Navy's (RN) Fleet Air Arm (FAA). The school trained volunteers from the

local territorial units using Luscombe seaplanes (see photo) paid for by an

American resident of Bermuda, Mr Bertram Work, and a Canadian, Mr Duncan

MacMartin. Those who passed their training were sent to the UK's Air Ministry to

be assigned, as promised, to the Royal Air Force (RAF) or the Royal Navy's Fleet

Air Arm (FAA).

It began

with the goal of training pilots for the Royal Air Force (RAF) or the Royal

Navy's (RN) Fleet Air Arm (FAA). The school trained volunteers from the

local territorial units using Luscombe seaplanes (see photo) paid for by an

American resident of Bermuda, Mr Bertram Work, and a Canadian, Mr Duncan

MacMartin. Those who passed their training were sent to the UK's Air Ministry to

be assigned, as promised, to the Royal Air Force (RAF) or the Royal Navy's Fleet

Air Arm (FAA).

The Commanding Officer of the school was Major Cecil Montgomery Moore, DFC, earlier the senior officer of the Bermuda Volunteer Rifle Corps, who had gone to the UK to serve as a fighter pilot during the First World War and who was also the commander of the Bermuda Volunteer Engineers. The chief flying instructor was an American, Captain Ed Stafford. The first class, of eighteen students, was in training by May 1940. On 4 June, Fenton Trimingham became the first student to solo. Ten Bermudian companies agreed in June 1940, to defray the expenses of ten of the students. They were the Bank of Bermuda, the Bank of N.T. Butterfield, Trimingham Bros., H.A. & E. Smith, Gosling Bros., Pearman Watlington & Company, the Bermuda Electric Light Company (BELCO), Bermuda Fire & Marine Insurance Company, the Bermuda Telephone Company (TELCO), and Edmund Gibbons.

The school trained eighty pilots before an excess of trained pilots led to its closure in 1942. The body administrating it was adapted to become a recruiting organisation for the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF), sending two-hundred aircrew candidates to that service before the war's end. The BFS only accepted applicants who were already serving in one of the part-time units, which had been mobilized for the duration of the war. Successful students were released from their units and allowed to proceed overseas. With the moratorium against sending drafts overseas, this meant local soldiers came to see the BFS as the easiest way of reaching sharper ends of the war. The BFS was included in the Empire Air Training Scheme for British Commonwealth pilots. Its graduates included eight Americans, who had volunteered for the RAF in the USA, and had then been sent to the BFS for training. Photo above right: Bermuda Flying School Luscombe parked next to a PAA aircraft.

Photo shows then-Duke of Windsor, third from right, in dark suit, formerly King Edward VIII, in Bermuda before he was sent as Governor of the Bahamas, inspecting the new Bermuda Flying School

![]()

They were graduates of the Bermuda Flying School which had been set up by the Royal Air Force then with a base in Bermuda. Some were bound for the UK's Royal Air Force. They left on the New Zealand Shipping Line mostly cargo vessel SS Mataroa. Others went to Canada, for service with the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF). They included

Other Bermudians too joined the RAF, as graduates of the Bermuda Flying School.

Those who went to Canada and joined the Royal Canadian Air Force included

Others, who joined separately included Martin Smith, later a Bermuda barrister, who did not graduate from the Bermuda Flying School but instead joined up while he was in the UK (See Bermuda Mid Ocean News article 25th March 1972).

![]()

A first for Bermuda, part of the construction from scratch of the US Military facilities in Bermuda - mostly US Army and US Army Air Force at St. David's and in St. George's and paid for 100% by American taxpayers. At the same time as simultaneous construction of the US Navy base in Southampton, ships and aircraft of the US Navy began to be based in Bermuda. Losses galore of US military aircraft began to occur in and around Bermuda from then to the end of the war.

![]()

The Brewster Bermuda was the name given by the RAF to the Brewster SB2A (below). In the US Navy service, the aircraft was the SB2A "Buccaneer." The Bermuda was not carrier-capable, although it was designed as a dive bomber.

Brewster Bermuda

![]()

Sunk in Great Sound when training local defenses.

![]()

Made in the USA in huge numbers. Acquired by the Royal Air Force After being ferried from Bermuda, it was destroyed in a bombing raid at Greenock and sank.

![]()

Mark IIb P8507 was bought for the Royal Air Force by Bermudians, by public appeal. It shot down five German aircraft before it failed to return on this date. Photo supplied to this author of Bermuda Online in 1986 from Royal Air Force records.

![]()

They were using Supermarine Walrus flying boats flown by naval pilots from ships at the dockyard, or pilots from the Royal Air Force and the Bermuda Flying School on Darrell´s Island. However, once the US Navy began flying air patrols from Darrell´s Island from September, the Fleet Air Arm´s patrols ceased.

![]()

United States Navy. Hit tent on Darrell's Island after missed approach.

![]()

Capsized on landing at Grassy Bay - but recovered.

![]()

It was not an American military plane but a British one. A Royal Air Force (RAF) B-24 Liberator landed on December 20, 1941 from Dorval, near Montreal in Canada. Almost immediately thereafter, Kindley Field became a transit stop for frequent shuttle RAF shuttle flights between Bermuda and the important Royal Air Force and Royal Canadian Air Force base established at Dorval.

![]()

After being licensed to fly in on September 11th, 1941, they departed Bermuda in January 1942 aboard the former passenger liner and now armed merchant cruiser " Queen of Bermuda". They included Lyall Mayor, Colyn L. Rees (born Spanish Point, Bermuda, November 25, 1922), Eddie Whitecross and John Pitt. They went to initially to Halifax, Nova Scotia for an overnight stay on their way to England. On departing Halifax, the ship went onto a reef during snow storm outside of Halifax harbour. Eventually, they arrived in England to join the RAF. Some had very interesting stories, with their aviation careers taking them all over the world.

![]()

Sank in Hamilton Harbour, later retrieved.

![]()

But did not fly it until 1946.

![]()

On board were a number of Bermudians bound for the Royal Canadian Air Force. They included Norman Sumpter, Harold Dale, Richards (first name unknown), Squires (first name unknown), Arthur (Copper) Jenkins, Charles Nunn, Robert Oatway, Fred (Red) Adderley, David Kopec, Herbert (Chummy) Zuill and Norman Jones. It was a 10-hour flight.

![]()

Sank during Bermuda storm but later retrieved.

![]()

Aircraft retrieved by freighter 100 miles off Bermuda and taken to San Juan.

![]()

HMS Newcastle, a Royal Navy ship damaged by a torpedo from a German submarine, slowly entered Bermuda under her own steam, en route to the Boston Navy Yard for substantial repairs. While in Bermuda and based at the Dockyard, she carried several Supermarine Walrus flying boats, one of which was launched on a training run. But the aircraft crashed into the sea of Daniel's Head and the rear gunner was killed.

![]()