Click on graphic above to navigate the 165+ web files on this website, a regularly updated Gazetteer, an in-depth description of our island's internally self-governing British Overseas Territory 900 miles north of the Caribbean, 600 miles east of North Carolina, USA. With accommodation options, airlines, airport, actors, actresses, aviation, banks, beaches, Bermuda Dollar, Bermuda Government, Bermuda-incorporated businesses and companies including insurers and reinsurers, Bermudians, books and publications, bridges and causeway, charities, churches, citizenship by Status, City of Hamilton, commerce, communities, credit cards, cruise ships, cuisine, currency, disability accessibility, Devonshire Parish, districts, Dockyard, economy, education, employers, employment, environment, executorships, fauna, ferries, flora, former military bases, forts, gardens, geography, getting around, golf, guest houses, highways, history, historic properties, Hamilton, House of Assembly, housing, hotels, immigration, import duties, internet access, islands, laws, legal system and legislators, main roads, marriages, media, members of parliament, money, motor vehicles, municipalities, music and musicians, newcomers, newspaper, media, organizations, parks, parishes, Paget, Pembroke, performing artists, residents, pensions, political parties, postage stamps, public holidays, public transportation, railway trail, real estate, registries of aircraft and ships, religions, Royal Naval Dockyard, Sandys, senior citizens, Smith's, Somerset Village, Southampton, St. David's Island, St George's, Spanish Point, Spittal Pond, sports, taxes, telecommunications, time zone, traditions, tourism, Town of St. George, Tucker's Town, utilities, water sports, Warwick, weather, wildlife, work permits.

![]()

By Keith Archibald Forbes (see About Us).

Advance information on Bermuda - from our files exclusively.

Of more than 1600 resident terrestrial plants and animal species, only 27% are native.

Bermuda's new Protected Species Act 2003 became law on 1st March 2004. Endemic animals are shown below by name and description. Except for birds, no prior legislation existed. The new act called for a proactive approach to the protection of local species threatened with extinction, and their habitats. Protected species include 27 plants, birds, animals and marine organisms, plus 21 cave organisms, as threatened and 'listed' according to international criteria. Recovery plans for the other species include the Bermuda Cedar, Palmetto and Yellowwood, plus fern and flowering plant species. Wildlife includes the Cahow, Longtail, White-eyed Vireo, Skink, turtles, whales, a species of snail, the tiny Cave Shrimp and other crustaceans. The Bermuda Protected Species Act 2003 allows for the listing of threatened species and recovery plans for active intervention, in order to enhance population levels. The Protected Species Recovery Plan project is funded by the UK Overseas Territory Environmental Programme (OTEP).

Fauna Bermuda does not have. There are no alligators, badgers, buffalo, chipmunks, crocodiles, deer, ferrets, giraffes, hedgehogs, lions, moles, mongooses, moose, raccoons, skunks, snakes, squirrels, stoats, tigers, weasels or zebras.

Flightless crane.

Flightless duck.

Hawk.

Fresh water limpets

Several species of rails.

Native ground nesting birds.

Two species of nesting sea turtles

Originally from Africa, Argentina, also Bermuda.

For decades, Bermuda has been the site of a

fierce — if tiny — war between rival species of ant. A recent scientific paper by James Wetterer of the Florida Atlantic University,

published in the Journal of Hymenoptera Research revealed that scientists have

recorded conflict between two invasive ant species — the African big-headed

ant and the Argentine ant — for more than 60 years as they battle for

dominance in Bermuda. While the African big-headed ant became the dominant ant species on the island in the early

20th century after being first recorded in 1889, the Argentine ant quickly began to claim territory

after arriving on the island in the 1940s. Both species are considered widespread and destructive, well-known for killing off native

invertebrates, particularly other ants. Dr Wetterer, who previously surveyed the

island’s ants in 2004 said most

of Bermuda’s ants were “tramp” species fighting each other for territory

on the island. According to Dr Wetterer’s findings, L humile was found

to be dominant across much of the island. However, a handful of battlegrounds

remain. At two long-term survey sites, found were both L humile and P

megacephala, on Ireland Island and the Newstead Belmont Hills Golf Resort

and Spa. On Ireland Island, were found P megacephala along

the North Breakwater and by the National Museum. In addition, P megacephala

were collected in front of the Clocktower Mall and to the south

end of the Glassworks Mall, two places occupied by L humile 14 years

earlier, indicating a modest expansion of the P megacephala population on

North Ireland Island. At the Newstead, was found the boundary between L humile

and P megacephala territory, near the western edge of the property,

essentially identical as 14 years earlier. At Newstead, collected in the

same vial were L humile and P megacephala workers from only a few

metres apart; the ants immediately locked in battle, confirming their mutual

intolerance. Also identified were four species of ant that

had not previously been reported on the island including Pheidole navigans,

who were spotted at multiple sights around the island. Given that the same areas

were searched in previous studies, it indicates that the species was a new

arrival. Curiously, at four of the five sites, P navigans was

coexisting with L humile. On Ordnance Island, they were found them nesting together under the same piece of concrete.

Not known is whether or not P megacephala can tolerate P

navigans.

For decades, Bermuda has been the site of a

fierce — if tiny — war between rival species of ant. A recent scientific paper by James Wetterer of the Florida Atlantic University,

published in the Journal of Hymenoptera Research revealed that scientists have

recorded conflict between two invasive ant species — the African big-headed

ant and the Argentine ant — for more than 60 years as they battle for

dominance in Bermuda. While the African big-headed ant became the dominant ant species on the island in the early

20th century after being first recorded in 1889, the Argentine ant quickly began to claim territory

after arriving on the island in the 1940s. Both species are considered widespread and destructive, well-known for killing off native

invertebrates, particularly other ants. Dr Wetterer, who previously surveyed the

island’s ants in 2004 said most

of Bermuda’s ants were “tramp” species fighting each other for territory

on the island. According to Dr Wetterer’s findings, L humile was found

to be dominant across much of the island. However, a handful of battlegrounds

remain. At two long-term survey sites, found were both L humile and P

megacephala, on Ireland Island and the Newstead Belmont Hills Golf Resort

and Spa. On Ireland Island, were found P megacephala along

the North Breakwater and by the National Museum. In addition, P megacephala

were collected in front of the Clocktower Mall and to the south

end of the Glassworks Mall, two places occupied by L humile 14 years

earlier, indicating a modest expansion of the P megacephala population on

North Ireland Island. At the Newstead, was found the boundary between L humile

and P megacephala territory, near the western edge of the property,

essentially identical as 14 years earlier. At Newstead, collected in the

same vial were L humile and P megacephala workers from only a few

metres apart; the ants immediately locked in battle, confirming their mutual

intolerance. Also identified were four species of ant that

had not previously been reported on the island including Pheidole navigans,

who were spotted at multiple sights around the island. Given that the same areas

were searched in previous studies, it indicates that the species was a new

arrival. Curiously, at four of the five sites, P navigans was

coexisting with L humile. On Ordnance Island, they were found them nesting together under the same piece of concrete.

Not known is whether or not P megacephala can tolerate P

navigans.

Argentine ant. Linepithema humile. Irodomyrmex humilus, numerous and a nuisance, can bite.

Bermuda Ant. Odontomachus insularis. An indigenous ant long thought extinct until re-discovered living in July 2002 by local college student Alex Lines, a Bermuda Aquarium Museum and Zoo intern.

Big Head Ant. Pheidole megacephala.

Carpenter Ant. Common in Bermuda. A nasty large ant, can eat through anything.

Bees

Bees were originally imported to Bermuda in 1616 from Britain. Local honey is very expensive compared to imported varieties but is lovely. The Bermuda Beekeepers' Association (BBA) was formed in 1949. Today, most of the island's beekeepers belong to BBA. One colony can produce up to 170 kg of honey. Local folklore says a teaspoon of Bermuda honey taken with tea is a powerful aphrodisiac. There are two honey flows a year, minor in June-July and major in September-October. In 2003, Hurricane Fabian caused substantial damage to the local honey industry, just at the start of the September honey flow. After it, no flowers were left from which bees could gather nectar. The effects of a hurricane linger for years while the vegetation recovers. In 1987 when Hurricane Emily swept over the island, the main honey flow from the Schinus sp. Brazilian pepper tree, was interrupted and approximately 30% of the island's vegetation destroyed. The annual honey crop was reduced by over 50%. Since then, bees have been further troubled by disease. In November 2009 an observant Bermuda beekeeper noticed an unexpected and new bee parasite in a sample of bees and comb removed from a feral (wild) hive. The parasite was confirmed to be Varroa mite, (Varroa destructor) – arguably the most destructive pest to the beekeeping industry and the one that has also been proposed as one of the several stressors that may be contributing to Colony Collapse Disorder (CCD). Scientists have predicted this mite will nearly eliminate our feral bee populations as well as having a devastating impact on kept (managed) bees. Recent surveys of local hives revealed that hundreds of hives are dying and the Varroa mite is the main suspect. Prior to the mite introduction there were estimated to have been several hundred wild bee colonies scattered around the island and approximately 310 kept hives. Bee specialists have advised that without any treatment or mite control, the bee population in Bermuda will dwindle down to about one hive every two kilometers (1.2 miles). That would be a total of 18 kept hives left in Bermuda. The effects on our environment especially on our agricultural crops and bee pollinated fruits could be catastrophic. In recent years, much attention has been focused on bees and their mysterious disappearance in areas of Europe and the United States. This phenomenon has been called (CCD) and as of yet no conclusive evidence has been found to prove that a single factor is the cause. Scientists believe that several factors combined, including viruses, mites, bacterial and fungal diseases, long-range hauling for pollination services and pesticide exposure may be stressing the bees’ immune systems, leading to the demise of bee colonies worldwide. In Bermuda, it often assumed wrongly that the island's distance from the USA as the nearest landmass offers some protection, but this is not so. In creating a bee friendly garden, select plants that attract bees. Not all lowers are attractive to bees and some are more attractive than others. Bees have a strong preference for purple, white and blue flowers, and some reds and oranges. Recommended for planting in the garden are bee-favorites cuphea (Mexican heather), alyssum, pentas, lantana and sunflowers. Try also herbs such as rosemary, thyme and mint or vegetables such as pumpkins and squashes. Bees are attracted to all these plants particularly when several of the same are planted together. Also, let your lawn be diverse in type. Bees like to feed on clover in the lawn.Leafcutter bee. Megachile spp. Extremely rare in Bermuda, known to inhabit Nonsuch Island. A native of the western USA. In Bermuda, most are approximately the size of the common honeybee, although they are somewhat darker with light bands on the abdomen. They also have different habits. Leafcutter bees are not aggressive and sting only when handled. Their sting is very mild, much less painful than that of honeybees or yellow jacket wasps. Leafcutter bees are solitary bees, meaning that they don't produce colonies as do social insects.

Leafcutter bee

Afforded protection under Bermuda's Protection of Birds Act 1975. Overall, only 23 birds breed in Bermuda, but there are over 200 different types of migrant birds that visit every year.

American coot. Fulica americana, common.

Belted Kingfisher. Ceryl alcyon. Once common in Bermuda.

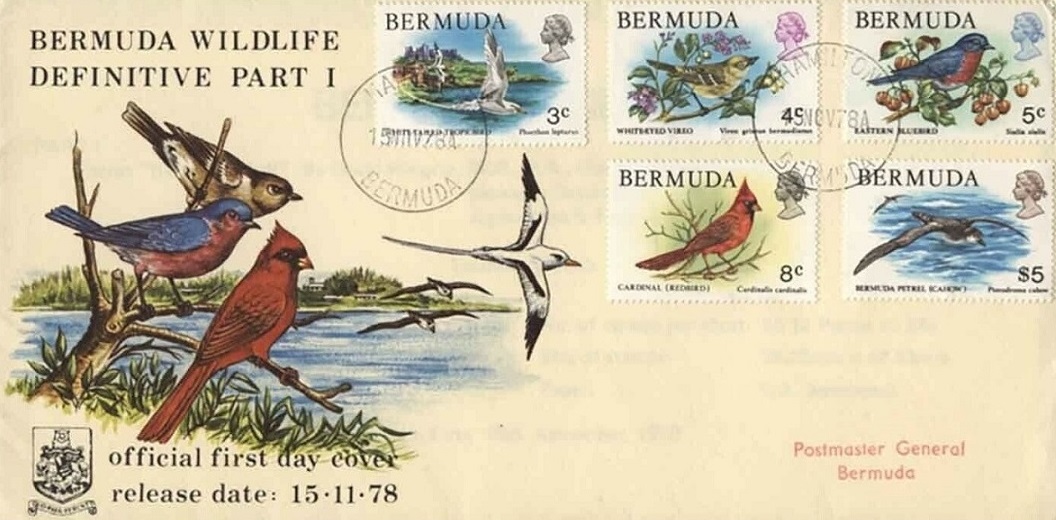

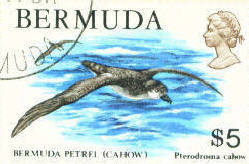

Cahow. Bermuda Petrel.

Pterodroma cahow.

(See 1978 Bermuda Postage

Stamp at right)A native, it was once prolific but consumed with gusto by early colonists. It was considered

extinct until quite recently. It is rare and

protected. It is believed to have been in Bermuda for 300,000 years.

Heard only during the winter months, the cahow earned its Christmas bird name from

mariners who became involuntary early temporary colonists after their ships

going elsewhere were damaged on the reefs. It is said that they were so

frightened by the nocturnal cries of this once abundant bird that they referred

to Bermuda as the Isles of Devils. When the first settlers arrived in 1609 and

1612, it is believed there were half a million cahows. They were so easy to

catch and eat they were hunted to what was thought to be extinction. In 1951, Dr. Cushman Murphy of

the USA finally arrived in Bermuda from a museum in New York City, after having

been pestered for years by Samuel Ristich to do so. Ristich had served in

Bermuda with the US Army Air Corps and had found a cahow. When Murphy came down,

he found five living cahows, believed to have been extinct since 1650. As a

direct result of Murphy's visit and unique find, Dr. David Wingate started his

breeding program for cahows on Nonsuch Island shortly afterwards. Dr.

David Wingate discovered 16 pairs still living on Nonsuch Island in 1951. In

2002, more than 65 breeding pairs were identified. They fly over

the sea but return to Bermuda to begin courtship activities in late

October. They mate for life and produce only one egg each year. The female lays a single white egg in January and in early March a

chick covered in dense grey down emerges. Young chicks leave Bermuda in late May

or early June and spend their first eight years of life on the open ocean before

returning as adults to breed. Like most petrels, cahows are nocturnal and land only to breed. They nest in a soil burrow the bird

excavates.

Cahow. Bermuda Petrel.

Pterodroma cahow.

(See 1978 Bermuda Postage

Stamp at right)A native, it was once prolific but consumed with gusto by early colonists. It was considered

extinct until quite recently. It is rare and

protected. It is believed to have been in Bermuda for 300,000 years.

Heard only during the winter months, the cahow earned its Christmas bird name from

mariners who became involuntary early temporary colonists after their ships

going elsewhere were damaged on the reefs. It is said that they were so

frightened by the nocturnal cries of this once abundant bird that they referred

to Bermuda as the Isles of Devils. When the first settlers arrived in 1609 and

1612, it is believed there were half a million cahows. They were so easy to

catch and eat they were hunted to what was thought to be extinction. In 1951, Dr. Cushman Murphy of

the USA finally arrived in Bermuda from a museum in New York City, after having

been pestered for years by Samuel Ristich to do so. Ristich had served in

Bermuda with the US Army Air Corps and had found a cahow. When Murphy came down,

he found five living cahows, believed to have been extinct since 1650. As a

direct result of Murphy's visit and unique find, Dr. David Wingate started his

breeding program for cahows on Nonsuch Island shortly afterwards. Dr.

David Wingate discovered 16 pairs still living on Nonsuch Island in 1951. In

2002, more than 65 breeding pairs were identified. They fly over

the sea but return to Bermuda to begin courtship activities in late

October. They mate for life and produce only one egg each year. The female lays a single white egg in January and in early March a

chick covered in dense grey down emerges. Young chicks leave Bermuda in late May

or early June and spend their first eight years of life on the open ocean before

returning as adults to breed. Like most petrels, cahows are nocturnal and land only to breed. They nest in a soil burrow the bird

excavates.

Catbird. Once common.

Common Tern. Sterna hirundo. The migratory bird thrives around the world, but the Bermuda population, which DNA analysis shows to be endemic and distinct, was almost wiped out by Hurricane Fabian in 2003 and in subsequent hurricanes. Terns typically lay eggs in clutches of three. Unlike the success story of the cahow, local terns are at the mercy of the elements before they head to their wintering grounds in South America. Partly for this reason, the tern has never been very common on Bermuda.

Egret. Visits frequently and some of the species are naturalized.

English house sparrow. Plain brown, common. Introduced in 1870.

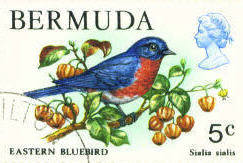

Eastern bluebird. Sialia sialis. Native. Once very common, it nested in hollows of cedar trees, on coastal cliffs and even under eaves of houses. As a cavity nester, it became especially vulnerable to nest site competition from the English house sparrow. With the Bermuda cedar spoilage in the 1950s and its repercussions, the population declined by more than 80%. An artificial wooden nest book program was introduced which has had limited success, but still a firm favorite among many Bermudians and other residents. Loves concrete bird baths with lots of water and can splash around in them for ages. This Bermuda postage stamp below of yesteryear honors them.

Great Blue Heron (Ardea herodias).

Kiskadee Flycatcher. Pitangus

sulphuratus. Noisy, aggressive,

yellow breasted and striped headed

shown in right graphic, known in American books on birds as the Great

Kiskadee. It has contributed to serious declines of the native

species chick-of-the-village, Northern cardinal and catbird. It is a very large, big-headed

flycatcher, near size of a Belted Kingfisher, somewhat like that bird in

actions, even catching small fish. It has rufous wings and tail. The bright

yellow under parts and crown patch and strikingly patterned black and white face

identify it. The local variety were imported from

Trinidad in 1957 as worker-birds in hope they would be beneficial. Their

hoped-for

function was to control - by consumption - the Anolis lizards which had incurred

a bad reputation from their diet of ladybirds. But they did nothing to

control the lizards. They are now

among the most common birds in Trinidad. They are also natives of other

Caribbean islands including Barbados, southern Texas

and Louisiana, south to Argentina and residents of the lower Rio Grande Valley. They

very rarely stray north to Arizona from western Mexico. Its bright pattern

is unique in North America. It is omnivorous. It feeds mostly

on large insects, such as beetles, wasps, grasshoppers, bees, and moths; but

also eats lizards, mice, baby birds, frogs, tadpoles, and small fish, many

berries, small fruits and some seeds. It forages in various ways, often going

from its perch flies out from its perch to catch flying insects in the air. It

will perch on branch low over water and plunge into water for fish, tadpoles, or

insects. It often eats berries in trees and shrubs. Both female and male mates

actively defend nesting territory against intruders of their own species and are

quick to mob any predators that venture too close. The nesting site is usually

among dense branches of a tree or large shrub, 6-50' above the ground, usually

10-20' up. The nest is a large bulky structure, more or less round, with the

entrance on the side. Nest is built of grass, weeds, strips of bark, Spanish

moss, and other plant fibers, and lined with grass. The female usually lays 4

eggs, sometimes 2-5. They are creamy white, dotted with dark brown and lavender.

Both adults help to feed the young in the nest. Without

knowing it beforehand, with the kiskadees Bermuda allowed in a veritable bird gang of terrorists. Those 200 original yellow-breasted kiskadees

have become the

prolific and noisy Mafioso of Bermuda's bird lands, trees, shrubs and telephone

wires - and a major threat to the lives, feeding and nesting habits of Bermuda's

beautiful bluebirds and other birds as well as to soft-skinned local fruit, crabs, fish and

other choice edibles. Also, they were the major reason for the extinction

of the endemic Cicada (known locally as Singers) by the late 1990s.

Kiskadee Flycatcher. Pitangus

sulphuratus. Noisy, aggressive,

yellow breasted and striped headed

shown in right graphic, known in American books on birds as the Great

Kiskadee. It has contributed to serious declines of the native

species chick-of-the-village, Northern cardinal and catbird. It is a very large, big-headed

flycatcher, near size of a Belted Kingfisher, somewhat like that bird in

actions, even catching small fish. It has rufous wings and tail. The bright

yellow under parts and crown patch and strikingly patterned black and white face

identify it. The local variety were imported from

Trinidad in 1957 as worker-birds in hope they would be beneficial. Their

hoped-for

function was to control - by consumption - the Anolis lizards which had incurred

a bad reputation from their diet of ladybirds. But they did nothing to

control the lizards. They are now

among the most common birds in Trinidad. They are also natives of other

Caribbean islands including Barbados, southern Texas

and Louisiana, south to Argentina and residents of the lower Rio Grande Valley. They

very rarely stray north to Arizona from western Mexico. Its bright pattern

is unique in North America. It is omnivorous. It feeds mostly

on large insects, such as beetles, wasps, grasshoppers, bees, and moths; but

also eats lizards, mice, baby birds, frogs, tadpoles, and small fish, many

berries, small fruits and some seeds. It forages in various ways, often going

from its perch flies out from its perch to catch flying insects in the air. It

will perch on branch low over water and plunge into water for fish, tadpoles, or

insects. It often eats berries in trees and shrubs. Both female and male mates

actively defend nesting territory against intruders of their own species and are

quick to mob any predators that venture too close. The nesting site is usually

among dense branches of a tree or large shrub, 6-50' above the ground, usually

10-20' up. The nest is a large bulky structure, more or less round, with the

entrance on the side. Nest is built of grass, weeds, strips of bark, Spanish

moss, and other plant fibers, and lined with grass. The female usually lays 4

eggs, sometimes 2-5. They are creamy white, dotted with dark brown and lavender.

Both adults help to feed the young in the nest. Without

knowing it beforehand, with the kiskadees Bermuda allowed in a veritable bird gang of terrorists. Those 200 original yellow-breasted kiskadees

have become the

prolific and noisy Mafioso of Bermuda's bird lands, trees, shrubs and telephone

wires - and a major threat to the lives, feeding and nesting habits of Bermuda's

beautiful bluebirds and other birds as well as to soft-skinned local fruit, crabs, fish and

other choice edibles. Also, they were the major reason for the extinction

of the endemic Cicada (known locally as Singers) by the late 1990s.

Flamingos. Not native, can be seen at the Bermuda Aquarium.

Herons. Great Blue Heron. Ardea herodias. Once common in Bermuda. Yellow crowned night herons (Nyctanassa violacea), once brought in to keep down the land crab population, were re-established from 46 birds imported from Florida in the 1970s. Now native.

Mourning dove. Zenaida macroura, Common. Similar to a wood pigeon.

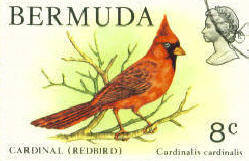

Northern cardinal. Cardinalis cardinalis. Bermudians know it as the Redbird. First introduced to Bermuda from Virginia in about 1700 as a cage bird, but once released became such a farm pest that bounties were offered for its capture. It became so abundant that during the 19th century many thousands locally were trapped for resale abroad as cage birds. Not all that common today, despite being officially protected. A favorite for many, it has bright red plumage and a loud cheery song. Likes bird feeders and has a preference for sunflower seeds.

1978 Bermuda Postage Stamp of Northern Cardinal.

Northern Waterthrush. Seiurus noveborancensis. Once common in Bermuda.

Pied-billed grebe. Podilymisus podiceyps. Common.

Starling. Introduced in the 1950s. An invasive which feeds on the fruits of the hugely invasive Indian Laurel tree and spreads even more invasive seeds throughout Bermuda.

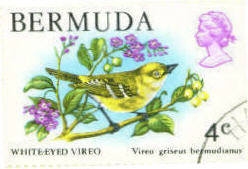

White-eyed virio. Vireo griseus bermudianus. Known to Bermudians as Chick of the Village in imitation of its cheery song which is sung throughout the year. An endemic sub-species characterized by shorter wings and duller plumage compared to its American first cousin. An insect-eating bird of the forest canopy, it was originally associated with Bermuda’s once-large, long-gone cedar and palmetto forest. The almost total destruction of the Bermuda cedar tree in the 1940s and 1950s by accidentally introduced insect pests nearly caused its extinction, but it has recovered.

1978 Bermuda Postage Stamp of this bird

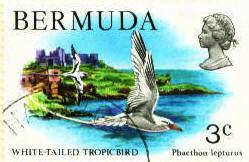

White-tailed yellow-billed tropicbird, better known as the longtail. Phaethon lepturus catesbyi. Bermuda's national endemic bird.

Graphic to the left from a 1978 Bermuda Postage Stamp shown at right below.

Despite its abundance along Bermuda’s coastline, the white-tailed tropic bird is prone to numerous threats that continuously inhibit their

reproductive success. Such threats include fierce hurricanes, which have been responsible for the loss of tropicbird nest locations through erosion and

cliff collapse. In 2003 Hurricane Fabian, a category 3 storm, was responsible for an estimated loss of 300 white-tailed tropicbird nest sites within

] the Castle Harbour islands of Bermuda. Hurricanes Felix and Adrian in September 2004 destroyed many nests and filled others

with rock. Threats to white-tailed tropicbirds are not just limited to natural disasters. There have been

instances of invasive species competing with Bermuda’s tropicbirds for nest sites. The invasive domestic pigeon (Columba livia), is known to utilize

crevices within cliff faces and rocky shorelines, effectively occupying potential nesting sites for Bermuda’s national

bird. Not indigenous but native. It is a

national symbol and many souvenirs and pieces of jewelry are made with its

image, some locally in gold and silver. The longtail as Bermudians know it is Bermuda’s traditional harbinger of spring

and one of the most beautiful features of our coastline during the summer

months. Nesting from April to October in holes and crevices of the coastal

cliffs and islands - mostly in the Castle Harbour islands - where it is

safer from human disturbance and introduced mammal predators, it is the only

native seabird to have survived in numbers comparable to its primeval abundance

on Bermuda. Once, up to about 1978, at least

3,000 nesting pairs used to breed along most of the coastline but the numbers

have declined steadily due to coastline development, increased disturbance from

an expanding population, and predation by illegally-stray stray dogs, cats,

crows and oil pollution at sea. Other factors include global warming and its higher sea levels that flood

lower nest sites. There is a longtail housing crisis.

To try to solve the problem of

weather, nature and global warming, longtail igloos were invented in 1997 as an

emergency measure to provide alternative nesting sites. They are made of SKB

roofing material and provide good insulation and shelter from the sun. They are

light but strong with a concrete covering that provides camouflage and holds the

nest in place. 35 longtail igloos are now in place on Nonsuch Island and seem to

be working well. Longtails have such small feet

that they are unable to walk on land and hence do all their nest searching on

the wing. It is this constant searching back and forth along the cliffs,

combined with their aerial courtship display, which involves touching the tips

of the long tail feathers together in paired flight, that makes them so

conspicuous on our coastline. The single purplish-red speckled egg is laid in

April and hatches in late May. The chick takes approximately 65 days to fledge

and departs to sea on its own in late July or early August. Longtails do all of their feeding

far out on the open ocean where they plunge from a height onto

unsuspecting fish and squid like a gannet. During the winter months, the

population disperses throughout the Sargasso Sea and remains out of sight of

land. Evidently, the birds sleep on the wing or on the water if it is calm.

Despite its abundance along Bermuda’s coastline, the white-tailed tropic bird is prone to numerous threats that continuously inhibit their

reproductive success. Such threats include fierce hurricanes, which have been responsible for the loss of tropicbird nest locations through erosion and

cliff collapse. In 2003 Hurricane Fabian, a category 3 storm, was responsible for an estimated loss of 300 white-tailed tropicbird nest sites within

] the Castle Harbour islands of Bermuda. Hurricanes Felix and Adrian in September 2004 destroyed many nests and filled others

with rock. Threats to white-tailed tropicbirds are not just limited to natural disasters. There have been

instances of invasive species competing with Bermuda’s tropicbirds for nest sites. The invasive domestic pigeon (Columba livia), is known to utilize

crevices within cliff faces and rocky shorelines, effectively occupying potential nesting sites for Bermuda’s national

bird. Not indigenous but native. It is a

national symbol and many souvenirs and pieces of jewelry are made with its

image, some locally in gold and silver. The longtail as Bermudians know it is Bermuda’s traditional harbinger of spring

and one of the most beautiful features of our coastline during the summer

months. Nesting from April to October in holes and crevices of the coastal

cliffs and islands - mostly in the Castle Harbour islands - where it is

safer from human disturbance and introduced mammal predators, it is the only

native seabird to have survived in numbers comparable to its primeval abundance

on Bermuda. Once, up to about 1978, at least

3,000 nesting pairs used to breed along most of the coastline but the numbers

have declined steadily due to coastline development, increased disturbance from

an expanding population, and predation by illegally-stray stray dogs, cats,

crows and oil pollution at sea. Other factors include global warming and its higher sea levels that flood

lower nest sites. There is a longtail housing crisis.

To try to solve the problem of

weather, nature and global warming, longtail igloos were invented in 1997 as an

emergency measure to provide alternative nesting sites. They are made of SKB

roofing material and provide good insulation and shelter from the sun. They are

light but strong with a concrete covering that provides camouflage and holds the

nest in place. 35 longtail igloos are now in place on Nonsuch Island and seem to

be working well. Longtails have such small feet

that they are unable to walk on land and hence do all their nest searching on

the wing. It is this constant searching back and forth along the cliffs,

combined with their aerial courtship display, which involves touching the tips

of the long tail feathers together in paired flight, that makes them so

conspicuous on our coastline. The single purplish-red speckled egg is laid in

April and hatches in late May. The chick takes approximately 65 days to fledge

and departs to sea on its own in late July or early August. Longtails do all of their feeding

far out on the open ocean where they plunge from a height onto

unsuspecting fish and squid like a gannet. During the winter months, the

population disperses throughout the Sargasso Sea and remains out of sight of

land. Evidently, the birds sleep on the wing or on the water if it is calm.

Yellow-crowned night heron (Nyctanassa violacea).

Common. Species include

Bermuda Buckeye (Junonia coenia bergi, endemic)

Cabbage (Pieris rapae)

Cloudless Sulphur (Phoebis sennae)

Gulf fritallary (Agraulis vanillae)

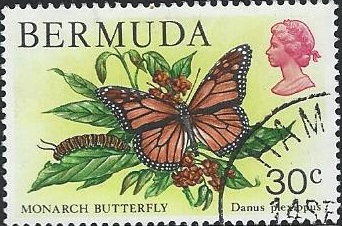

Monarch (Danus plexippus). One of several Bermuda butterfly residents, non-migratory, believed to have been established here by the mid 19th century. Bermuda also receives occasional visits from migratory North American Monarchs, known for their epic Winter treks across the continent to warm-weather locations in Mexico. Has bright orange wings with wide black borders and black veins; its hind wing has a patch of scent scales and white spots on its borders and apex. The typical wing span is 3.4 to 4.8 inches. The common name “Monarch” was first published in 1874 by Samuel H. Scudder. It is one of the largest of Bermuda's butterflies. The Monarch caterpillar has alternating yellow, white and black stripes. The caterpillar feeds solely on the leaves and flowers of Milkweeds, the butterfly on nectar from Milkweeds as well as other flowers. The Monarch Butterfly’s preferred habitats in Bermuda includes fields, gardens, meadows, weedy areas and marshes. Has appeared on a 30 cents Bermuda postage stamp.

Common, from the butterflies above.

Domestic and feral. No distinctive Bermudian kind. Many different types, mostly shorthair. Perhaps the most famous Bermuda cat was a once-feral mostly grey cat rescued by a Bermudian couple with aristocratic origins. He then got a name for the first time, Mr. Grey. but was so nice to his new parents that he was promoted to His Honor Mr Grey, then Lord Grey, then Earl Grey, then King Grey then Emperor Grey. Interestingly, cats are unique in the English language for having hugely more words beginning with "cat" than with "dog." This same couple has written a book about a once-prominent cleric once known as Father Grey, then Monsignor Grey, then Bishop Grey, then Archbishop Grey then Pope Grey....

Bulls, cows, calves. No distinctive Bermudian kind. Not many, not much farmed for meat, only for milk.

Anthropods.

Not too common. Several types. Once known to inhabit mainly eastern parishes and from this

often called the St. David's centipede, (see below). But some individual or nests of

centipedes have gotten around the Island via the trash collection system or

on horticultural debris collected from parks or woodland areas. Huge, can be

a foot long.

A bite can be painful and prolonged. They could cause serious problems

to anyone allergic to bee or insect stings. They feed on small insects, and

their venom, delivered by powerful pincers at their head, is said to be

about as painful as a bee sting. Have no qualms about entering homes

and guest units. The

best-known deterrent is having toads nearby, especially female ones. But

there are now far fewer toads than in the past. Centipedes usually

enter houses by accident while seeking prey, and end up trapped — although

they will make nests in damp, cool, protected areas. They can be dissuaded

from entering a residence by keeping tall vegetation and debris back from

walls.

Anthropods.

Not too common. Several types. Once known to inhabit mainly eastern parishes and from this

often called the St. David's centipede, (see below). But some individual or nests of

centipedes have gotten around the Island via the trash collection system or

on horticultural debris collected from parks or woodland areas. Huge, can be

a foot long.

A bite can be painful and prolonged. They could cause serious problems

to anyone allergic to bee or insect stings. They feed on small insects, and

their venom, delivered by powerful pincers at their head, is said to be

about as painful as a bee sting. Have no qualms about entering homes

and guest units. The

best-known deterrent is having toads nearby, especially female ones. But

there are now far fewer toads than in the past. Centipedes usually

enter houses by accident while seeking prey, and end up trapped — although

they will make nests in damp, cool, protected areas. They can be dissuaded

from entering a residence by keeping tall vegetation and debris back from

walls.

St David's Centipede. (Scolopendra subspinipes). This large centipede, known locally as such but also called the Tropical Centipede, has roamed the island for many years but is not found only in St David's. Individuals or nests of centipedes can easily get to all parts of Bermuda the island via the efficient trash collection system or on horticultural waste collected from parks or woodland areas. Centipedes feed on small insects and in most cases are regarded as beneficial to the gardener. The centipedes commonly found in the garden are appropriately named Garden Centipedes. These are approximately two to three inches long and should not be confused with the much larger Tropical Centipede, as the Garden Centipede is harmless. Another of the smaller local centipedes is the House Centipede, similar in size to the Garden Centipede, but with long spindly legs and, as the name suggests, is often found inside the house or similar buildings. The largest of Bermuda's centipedes attracts the most attention. The Tropical Centipede has powerful pincers under the head that contain venom used to subdue the prey and they will use them to give a painful “bite” if provoked. The bite is said to be similar to the average bee sting and does not pose any serious health risks for a healthy adult, but some individuals (the elderly, young or unwell) may be sensitive to bites of this sort and need to seek medical advice. This centipede is mostly nocturnal, but may be seen in the daytime if it has been disturbed. It feeds on small insects, spiders and occasionally earthworms. Tropical Centipedes prefer to reside and make nests in damp, cool, protected areas such as under leafy debris, log piles, in old Bermuda walls and wild woodland areas. Any old tree stumps or unkempt garden areas are good homes for centipedes. They may enter into houses in search of a dark, cool place to hide. Clearing out untended garden areas and removing stones and dead vegetation will reduce the chances of centipedes finding suitable homes in these areas. Centipedes have also been reported to make nests in abandoned piles of building sand.

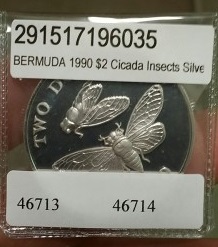

Tibicen

bermudiana Verrill (T. bermudianus for genus and species names to agree,

perhaps also now Neotibicen bermudianus) was an endemic Bermuda cicada but

is now extinct.

Tibicen

bermudiana Verrill (T. bermudianus for genus and species names to agree,

perhaps also now Neotibicen bermudianus) was an endemic Bermuda cicada but

is now extinct.

Its closest relative is the Tibicen lyricen, which is found in mostly the United States (and not extinct, seen and heard there, often with mixed views). Until the 1950s, Bermuda had Bermuda red cedar trees -different to Virginia cedar - galore, which cicadas loved.

The sound of the cicada love song, amorous adult males wooing ready females, was for many years in Bermuda the loudest and most wonderful insect song at night, louder and more tuneful to adults than the sounds of tree frogs.

Bermudians referred to cicadas fondly, often as "hummers" after the persistent humming cicada song or usually more romantically as "singers". Some species of cicadas then known in Bermuda registered over 100 decibels when singing.

Sadly, when most of the Bermuda cedar trees were killed of by a blight in the 1950s, the cicadas that made the nights so uniquely magical and romantic in sound also largely disappeared. Bermudians, those over 75 in particular, have mourned their loss ever since There are two (right and below) photos of a T.bermudiana at the Staten Island Museum in New York. One shows the Bermuda dollar $2 silver cicada coin of 1990 issued by the Bermuda Monetary Authority and the other is a rather splendid photograph of a preserved Bermuda cicada or "singer" at the Staten Island Museum, as discovered in and brought back from Bermuda by a Mr. Schwarz of that museum.

Usually

Megaloblatta blameroides or Blattella asahinai - giant

flying ones, easily as large as or larger then the Texas variety, or

Periplaneta americana or Blattella germanica - that fly and can get into even the most impeccably maintained

apartments, condominiums and cottages and are extremely difficult to

get rid of. Numerous and a nasty nuisance,

especially in the kitchen and bedrooms, particularly when the later not

air-conditioned.

Usually

Megaloblatta blameroides or Blattella asahinai - giant

flying ones, easily as large as or larger then the Texas variety, or

Periplaneta americana or Blattella germanica - that fly and can get into even the most impeccably maintained

apartments, condominiums and cottages and are extremely difficult to

get rid of. Numerous and a nasty nuisance,

especially in the kitchen and bedrooms, particularly when the later not

air-conditioned.

They like the combined heat and humidity of Bermuda for most of the year. But in fairness to Bermuda they are not Bermudian except by naturalization. They are also common throughout the Caribbean (900 miles to the south) plus in Florida, Texas, etc.

They are despised by everyone, with tourists often so shocked to see them that their whole trip is spoilt. Before tourists pack up to leave Bermuda they should check to see they do not accidentally pack cockroaches too, as they are often found in suitcases or luggage, still alive, hungry and irritable, causing bad memories of particular trips.

Some

can grow 3 inches or more long. These cockroaches resist

being squished, can live for days even when their heads are cut off, breed with hen roaches and have numerous families of

chick roaches. Some can stink when they are dead. Best way of trying to keep them at bay is to use Raid roach

spray.

Dogs

No local breeds. All must be leashed by law when out and about but this is often ignored. All must be licensed. There are several local dog organizations and annual dog shows in Bermuda attracting participants from the USA and Canada mostly.

Horses, mostly for show or recreation or limited agricultural purposes. There are also ponies for racing and showing, donkeys and mules

Fishes of Bermuda publication. 1999. Updated in 2013. There are many types of sea fish found in Bermuda, all similar to what are found off Florida and in the Caribbean, several of which are indigenous to Bermuda. There are also blackish pond fish, killifish (see below), several of which are unique to Bermuda. In sea fish, wahoo and yellowfin tuna are two of the most important species. Traditionally caught during their spring and fall "runs", these species pass by Bermuda during annual migrations that take them throughout the central Atlantic, although small individuals may remain in the area through the summer. It is thought that the Bermuda Seamount is an important feeding stop for these species during their long migratory journeys.

Atlantic Pearl Oyster. Pinctada imbricata.

Barracuda (Sphyraena barracuda).

Barred Hamlet (Hypoplectrus puella)

Beaugregory (Stegastes leucostictus)

Bermuda Bream (Diplodus bermudensis)

Bermuda Cave Fauna. Various species.

Bermuda Chub (Kyphosus sectatrix)

Bermuda Cone Conus mindanus.

Bermuda Creole Wrasse. Clepticus parrae. In 2013 this species was declared by the Smithsonian Institution to be endemic to Bermuda but closely allied to its Caribbean cousin.

Bermuda Fireworms or Glowworms. Odontosyllis enopla. On August 17, 2018 US researchers shone a light on Bermuda’s glow worms. Scientists at the American Museum of Natural History discovered the chemical that gives the Bermuda fireworms their glow is unique. The published study found that a “luciferase enzyme” created the distinctive glow — but the chemical is different from those found in other “glowing” animals like fireflies. Michael Tessler, a postdoctoral fellow in the museum’s Sackler Institute for Comparative Genomics, added the discovery could be useful in future research. He said: “It’s particularly exciting to find a new luciferase because if you can get things to light up under particular circumstances, that can be really useful for tagging molecules for biomedical research.” Bermuda fireworms, found around the island and throughout the Caribbean, gain their name from their seasonal breeding display in which swarms of the animals light up. The phenomenon was first recorded by explorer Christopher Columbus, and takes place minutes after sunset on the third night after the full moon in the summer and autumn. Spawning female fireworms release a bright bluish-green luminescence intended to attract males. Mark Siddall, a curator in the museum’s Division of Invertebrate Zoology and a coauthor of the study, said: “The female worms come up from the bottom and swim quickly in tight little circles as they glow, which looks like a field of little cerulean stars across the surface of jet black water. Then the males, homing in on the light of the females, come streaking up from the bottom like comets, they luminesce, too. There’s a little explosion of light as both dump their gametes in the water. Lovely to see but not to touch, bright orange worm fringed by white bristles, the latter to discourage predators, to avoid penetration of the skin and a rash or worse do not pick up. Often scarce except in summer, can shine several times a year, including in August, especially at Ferry Reach. They produce a fine light display in shallow sandy waters, especially in its mating ritual. It is at its best on the third night after the full moon on a warm summer night and 53 minutes after sunset. Glowworms inhabit protected bays, living in silky mucus tubes amongst the sediment of rock-strewn seabeds.

Often overlooked except on summer nights they dazzle onlookers with their magnificent natural light show. Female worms leave the safety of the rocky bottom and swim to the surface where they swarm in circular patterns, releasing a bright green luminescent substance intended to attract males. The rings of bright green light are amazing, but the light show gets even better when excited males make a frenzied dash towards their female targets. Upon making contact, males and females release an explosion of glowing gametes into the water in their sexual frenzy. The display lasts about 10 minutes. Males and females squirm and sperm in an orgasmic sudden green flash. The shallow bays of the panting sea creatures light up. Then suddenly they shudder, gasp and are still. Sites for the show, not near electric lights, have included the small bridge at the end of Ferry Reach Park, St. David's, Flatts and Ely's Harbour. Viewing is best three nights after a full moon. Fewer and fewer worms join in on succeeding nights. They only spawn at full moon, the girls literally 'light up' at the prospect of finding a mate, and dozens of tourists hang out in boats to watch them at it. This is the weird and wonderful world of Bermuda's famous fireworms. They generally "dance and mate" between early August and early September. The female fireworm emits her strikingly beautiful green light as she whirls frantically in circles to attract a mate. She releases her glowing eggs when he darts up and reaches the 'bull's eye' of her circle, producing a bright flash himself as he releases his sperm. According to scientific studies, it's a common occurrence for several males to be attracted to a single female, which results in them all rotating in a tight circle as the males discharge their sperm into the water. Spawning begins at full moon and reaches a peak three days afterwards. The females appear at the water's surface between 51 and 63 minutes after sunset in a display that only lasts a few minutes. The mesmerizing fireworms are actually marine relatives of the familiar earthworm and their Latin name – Odontosyllis enopla – translates as the toothed and necklaced worm." The creatures are only ten to 20 millimeters long and inhabit the sandy bottoms of Bermuda's bays and inlets, with Ferry Reach being one of the best spots to see them, according to seasoned worm watchers. The males are smaller than the females but have larger eyes, in keeping with their sensitivity to the light given off by the females. According to They are "equally stimulated by the beam from a flashlight. The green glow emitted by the fireworms – found throughout the tropical western Atlantic – is the product of bioluminescence, a light produced by a chemical reaction in a living organism. They only produce their dance of light during mating activities – although some scientists have observed that they also glow in response to being startled. Little is known about what exactly triggers the mating ritual which can be predicted with extraordinary accuracy and much mystery still surrounds these fascinating creatures. It's even been suggested that they were responsible for the strange patches of light seen by Christopher Columbus four hours before he first made landfall in America.

Bermuda Halfbeak (Hemiramphus bermudensis).

Bermuda killifish. Fundulus bermudae. Lives in both brackish and saltwater ponds from Hamilton Parish to Somerset. They are sometimes referred to as ‘mangrove minnows.

Black Grouper. Mycteroperca bonaci. A large bony reef fish species and an important component of the local fishery.From data collected it is now known that they can live for at least 33 years and that they change sex from female to male.

Black Sea Squirt. Phallusia nigra.

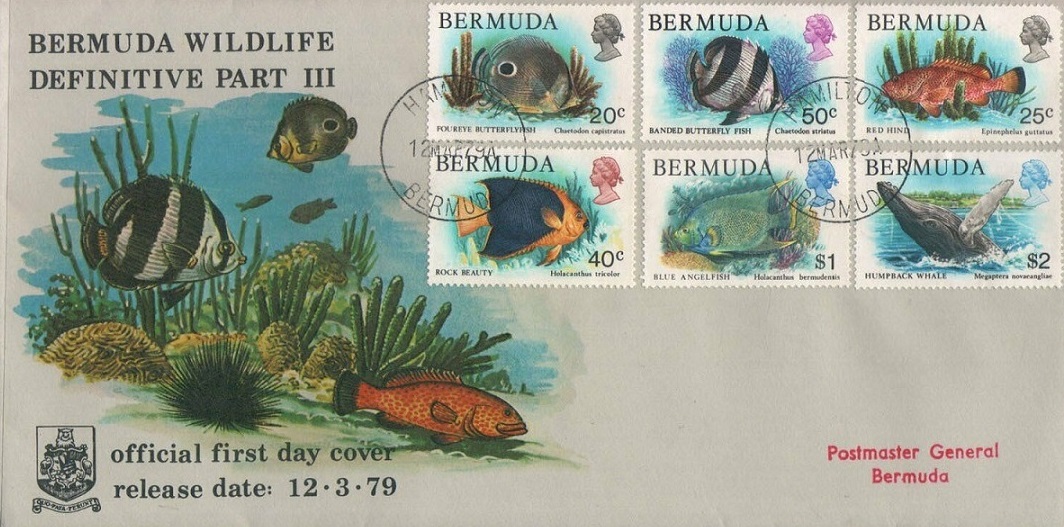

Blue Angel Fish. Holacanthus bermudensis. Shown on the March 12, 1979 Bermuda postage stamp above. A species of marine angelfish of the family Pomacanthidae. Should not be confused with Holocanthus ciliaris, or queen angelfish, despite very similar appearances. They are two separate species.

Blue Fry (Jenkinsia lamprotaenia)

Blue-Striped Grunt (Haemulon sciurus).

Blue-Striped Lizardfish (Synodus saurus)

Bonefish (Albula vulpes).

Brown Zoanthid. Palythoa variabilis.

Calico Clams. Macrocallista maculata. A marine bivalve mollusk of the genus Macrocallista, especially M. nimbosa, having a smooth, thick, rounded shell marked with violet-brown or lilac spots or streaks. Not to be confused with scallops, these were once reared in Harrington Sound, in a Bermuda Government project. A protected species since 1978. They live under the sand.

Calico Scallops. Argopecten gibbus. A species of medium-sized edible saltwater clam, specifically a scallop, a marine bivalve mollusk in the family Pectinidae. Sometimes known as Zigzag scallops, featured on a recent 45 cent Bermuda stamp, once reared in Harrington Sound, in a Bermuda Government project. They have been a protected species since 1978 in Bermuda but are eaten readily in other places such as Florida where they are common.

Chicken Liver Sponge. Chondrilla nucula.

Christmas Tree Worm (Pomatoceros triqueter).

Chitons or suck rocks. Common.

Colettes Halfbeak. In 2014 the Smithsonian Institution declared this species of fish was endemic to Bermuda.

Common Octopus. Octopus vulgaris.

Common Plateweed (Halimeda incrassata).

Conch. Strombus costatus. Residents and visitors should note that under the Fisheries (Protected Species) Order 1978, the Queen Conch (Strombus Gigas) and the Harbour Conch (Strombus Costatus) are illegal to import, an offence to purchase and possess and illegal to obtain and take from Bermuda waters. The Queen Conch - the first of several endangered native species to receive Government protection. Strombus gigas was abundant in Bermuda until the late 1960s but by the end of the Seventies, populations had reached very low levels. At present, most of the Queen Conch in the Island's waters are 'old individuals', with substantial algal and coral growth. Few juveniles have been seen, raising concern for the species' survival. Although the species has been protected from removal from the water since the Fisheries Act 1978, it has only recently been listed under the Protected Species Act 2003 as "endangered". The Queen Conch is now the first subject of a series of action plans to conserve Bermuda's marine and terrestrial threatened species. Despite a complete ban from fishing and/or taking since 1978 under local laws, there has been no conservation programme for this species to date.

Crabs. In beach areas, also once on lawns and paths by the sea.

Disc Plateweed (Halimeda tuna).

French Grunt. Haemulon flavolineatum. A species of grunt native to the western Atlantic Ocean from South Carolina and Bermuda to Brazil as well as the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean Sea. Travels in schools among coral and rocky reefs where it occurs at depths of from 0 to 60 metres (0 to 197 ft). Body is yellow with horizontal silver stripes running the length of, and diagonally-oriented stripes below the lateral line of their bodies. All of the fins are yellow. The sounds they make when grinding their teeth earned them their common name. They use their swim bladders to amplify this sound.

Foureye Butterflyfish. Chaetodon capistratus.

Golfball Sponge or Tangerine Sponge. Tethya actinia.

Eels. There are several species of Eel found locally, some of which get mistaken for sea snakes. In particular, the Goldspotted Eel (Myrichthys ocellatus) is often mistaken for a sea snake. Look for the long dorsal fine that runs along the entire body of the eel. Sea snakes do not have dorsal fins. Eels procreate in Bermuda waters or in the Sargasso Sea nearby then swim 3500 miles to the UK. There is also the Chain moray eel (Echidna catenata).

Fantail Mullet (Mugil trichodon).

Fire Coral (Millepora alcicornis).

Flagfin Mojarra (Eucinostomus melanopterus).

Fire Sponge. Tedania ignis.

Five-Toothed Sea Cucumber (Actinopyga agassizi).

Glass shrimp. (4.5 cm), Common in tide pools but had to see, transparent except for pale brown lines running across them like tiger stripes. When you see one, you’ll usually soon see more.

Grape Sand Moss or Green Grape Alga (Caulerpa racemosa).

Green sea turtles. Chelonia mydas.

Once an abundant food source for Bermuda’s early settlers this reptile was

the subject of the Island’s first conservation law passed by Bermuda’s first

Parliament in 1620. This and subsequent measures were unsuccessful in preventing

the destruction of nesting colonies of turtles in Bermuda. Green turtles found

at Bermuda today are itinerant individuals from the Caribbean or were brought

from Costa Rica as eggs and incubated on beaches as part of a re-stocking

experiment. They have never been exclusive to Bermuda as some reports allege. Green turtles feed on sea grasses and any other marine life they can

catch such as jelly fish, crustaceans and fishes. Turtles mature at a weight of

about 200 lbs. and will crawl up on beaches at night to lay their eggs. All

species of marine turtles are protected by Bermuda’s Fisheries Act and all

have been the subject of research in recent years. Once on a $3 Bermuda postage

stamp. They are named for the hue of their skin, not their shells. Though

hatching sea turtles are very vulnerable and only a few survive to adulthood,

the only real threats to fully-grown turtles are sharks and humans. Turtles have

good sight underwater, but are thought to be near sighted on land. Their senses

of smell and hearing are impeccable. Adult turtles sleep at night by wedging

themselves in reefs, and can hold their breath for 4-7 hours. Female green sea

turtles return to the same nesting beach where they were hatched, probably with

the help of olfactory, magnetic, and celestial cues. The temperature of the sand

in which eggs are laid determines the sex of turtles. Cooler temperatures

produce male turtles, while warmer temperatures produce female turtles, and

because of Bermuda’s cool climate in comparison to other turtle breeding

zones, we will never have females returning to lay again. Bermudian green sea

turtles are at the second stage of their lives, where they become vegetarians

grazing on sea grass, and they can spend up to fifteen years here. After that,

they move on to adult foraging grounds and reach sexual maturity.

Green sea turtles. Chelonia mydas.

Once an abundant food source for Bermuda’s early settlers this reptile was

the subject of the Island’s first conservation law passed by Bermuda’s first

Parliament in 1620. This and subsequent measures were unsuccessful in preventing

the destruction of nesting colonies of turtles in Bermuda. Green turtles found

at Bermuda today are itinerant individuals from the Caribbean or were brought

from Costa Rica as eggs and incubated on beaches as part of a re-stocking

experiment. They have never been exclusive to Bermuda as some reports allege. Green turtles feed on sea grasses and any other marine life they can

catch such as jelly fish, crustaceans and fishes. Turtles mature at a weight of

about 200 lbs. and will crawl up on beaches at night to lay their eggs. All

species of marine turtles are protected by Bermuda’s Fisheries Act and all

have been the subject of research in recent years. Once on a $3 Bermuda postage

stamp. They are named for the hue of their skin, not their shells. Though

hatching sea turtles are very vulnerable and only a few survive to adulthood,

the only real threats to fully-grown turtles are sharks and humans. Turtles have

good sight underwater, but are thought to be near sighted on land. Their senses

of smell and hearing are impeccable. Adult turtles sleep at night by wedging

themselves in reefs, and can hold their breath for 4-7 hours. Female green sea

turtles return to the same nesting beach where they were hatched, probably with

the help of olfactory, magnetic, and celestial cues. The temperature of the sand

in which eggs are laid determines the sex of turtles. Cooler temperatures

produce male turtles, while warmer temperatures produce female turtles, and

because of Bermuda’s cool climate in comparison to other turtle breeding

zones, we will never have females returning to lay again. Bermudian green sea

turtles are at the second stage of their lives, where they become vegetarians

grazing on sea grass, and they can spend up to fifteen years here. After that,

they move on to adult foraging grounds and reach sexual maturity.

Grey Snapper (Lutjanus griseus). Once common in Bermuda. Good eater.

Hard Fan Alga (Udotea flabellum).

Hogfish (Lachnolaimus maximus).

Hogmouth Fry (Anchoa choerostoma).

Honeycomb Cowfish (Lactophrys polygonius).

Horse-eye Jack (Caranx latus).

Humpback Whale. Megaptera novaeangliae. Shown on the March 12, 1979 Bermuda postage stamp above. Bermuda is a sanctuary for whales - humpback, blue, northern - and dolphins in its 200 mile Exclusive Economic Zone under the Fisheries (Protected Species) Order of the Fisheries Act.

Ivory Bush Coral (Oculina diffusa)Ivory Tree Coral (Oculina valenciennesi).

Keyhole Sand Dollar. Often but erroneously referred to as the Bermuda Sand Dollar, the Keyhole refers to three species of sand dollar in the genus Mellita that are dispersed along the east coast of the United States from Virginia to Brazil and also found along the coasts of Bermuda, Jamaica, and Puerto Rico. Mellita isometra is found along the east coast of the United States, Mellita tenuis is found along the gulf side of Florida, Alabama, and Mississippi. Mellita quinquiesperforata is found from near the Mississippi Delta to Brazil. See it in shallow waters below tide lines in sandy bottoms, burrowing for protection from waves and predators, and to obtain food. It feeds on fine particles of organic matter they filter from the water. A flat version of a sea urchin, reaching up to three inches in diameter and disk-like in shape. It differs greatly from the closely related cousin, however: the underside is usually flat or concave with the mouth directly in the center and the anus to one side. Its mouth is made up of five teeth arranged in a circle that form what is called, "Aristotle's lantern". Its skeleton is called a test and covered with an epidermis, spines (used in burrowing), tube feet (used for locomotion), and cilia. On its upper surface, petalloids (used as gills), specialized tube feet, are arranged in a pattern favoring five flower petals. Five oval shaped holes, called lunules, pierce the tests in keyhole urchins. There are two pairs of lunules, one pair toward the top and one large longer hole in between the second pair toward the bottom. Coloration of the keyhole sand dollar varies, including tan, brown, and occasionally grayish or green hue. The Sand dollar pass through several life stages. After eggs have been fertilized they develop into swimming larvae. It drifts in the sea water as plankton for four to six weeks, filtering tiny organisms. Juvenile keyhole urchins grow into adults, and live on the ocean floor. Natural enemies of the keyhole sand dollar are bottom feeding fishes.

Lacy Sea Squirt. Botrylloides nigrum.

Lane Snapper (Lutjanus synagris).

Lesser Starlet Coral (Siderastrea radians).

Lionfish. Beautiful but potentially deadly poisonous fish. It found its way to Bermuda from the Pacific in 2001 and was reported in a local newspaper on December 28, 2001 when one was caught off a local beach. It is about 12 inches long and was introduced to the Atlantic. There have since been many sightings on Bermuda beaches. There are lots of different species. If you get one in your swim suit, you will be stung badly.

Lizardfish, Sand Diver (Synodus intermedius).

Lisa or White Mullet (Mugil curema).

Lobsters, spiny. Panulirus argus. When caught in or off Bermuda they are really crayfish. Not indigenous, same type as in Caribbean and Florida, see note below. Very expensive. Biggest ever caught in Bermuda was in 1932, with a weight of 16 lbs. Second biggest was in 1983 of 15 lbs and with an arm span of five feet eight and a half inches. It is against the law to catch any from April 1 to August 31 each year and at other times only by residents specifically licensed to do so. Commonly referred to as the Florida spiny lobster, the Caribbean spiny lobster inhabits tropical and subtropical waters of the Atlantic Ocean, Caribbean Sea, and Gulf of Mexico. Spiny lobsters get their name from the forward-pointing spines that cover their bodies to help protect them from predators. They vary in color from almost white to dark red-orange. Two large, cream-colored spots on the top of the second segment of the tail make spiny lobsters easy to identify. They have long antennae over their eyes that they wave to scare off predators and smaller antennae-like structures called antennules that sense movement and detect chemicals in the water. Adult spiny lobsters make their homes in the protected crevices and caverns of coral reefs, sponge flats, and other hard-bottomed areas. The lobsters spawn from March through August and female lobsters carry the bright orange eggs on their undersides until they turn brown and hatch. Larvae can be carried for thousands of miles by currents until they settle in shallow near-shore areas among sea-grass and algae beds. They feed on small snails and crabs. The lobsters are solitary until they reach the juvenile stage, when they begin to congregate around protective habitat in near-shore areas. As they begin to mature, spiny lobsters migrate from the nursery areas to offshore reefs. Lobsters hide during daylight hours to avoid predators, emerging a couple of hours after dark to forage for food. While lobsters will eat almost anything, their favorite diet consists mostly of snails, clams, crabs, and urchins. The lobsters return to the safety of their dens several hours before sunrise. It takes a spiny lobster about two years to grow to the three-inch carapace legal-harvesting size and they can grow as large as 15 pounds. Maine lobsters, not seen in local waters, are imported to Bermuda to eat, at restaurants. Once was on a 10 cent Bermuda postage stamp.

Longspine Squirrelfish (Holocentrus rufus).

Lover’s Lake killifish. Fundulus relictus. Found in saltwater ponds in the east end of the island. Fundulus relictus and Fundulus bermudae are considered endangered, and were added to the Bermuda-protected species list in January 2012 as level 2 protected species.

Mermaid’s Wine Glass (Acetabularia crenulata).

Merman’s Shaving Brush (Penicillus capitatus).Milky Moon Snail. Polinices lacteus. Marine snail.

Mollusks. Many, on the rocky shore. Largest is the West Indian Top Shell. Once eaten in quantity, now more common. A type of marine snail. With cream coloured shells and black spots.

Molly Miller (Scartella cristata).

Moon Jelly (Aurelia aurita).

Mussels. Arca zebra. Bermuda's turkey-wing shaped mussels. These attractive brown and white striped shells get their name because they are shaped somewhat like a turkey wing. They are the most abundant bivalve in Bermuda’s waters, and are most commonly sourced in Harrington Sound. These animals are found along the east coast of the United States from North Carolina to Florida, through the Caribbean and as far south as Venezuela. Turkey-wing mussels grow slowly to a maximum size of approximately 80 mm, and are thought to reach 10 years old! They are the principal ingredients in a traditional Bermuda mussel pie.

Netted Olive. Oliva reticularis. Marine snail.

Ocean Surgeonfish (Acanthurus bahianus).

Orange Sea Squirt (Ecteinascidia turbinata).

Palometa (Trachinotus goodei).

Peacock Flounder (Bothus lunatus).

Petticoat Alga (Padina vickersiae).

Portuguese Men of War. Physalia physalis. Not Bermudian but common in the Western Atlantic and Caribbean further south, in Bermuda especially on South Shore beaches. They are highly dangerous stinging jellyfish-like creatures and should be avoided like the plague. Type: Invertebrates. Diet: Carnivore. Size: Float: 12 inches long: 5 inches wide; tentacles: up to 165 feet long. Not jellyfish, siphonophores, animals made up of a colony of organisms working together. Each one has four separate polyps. They get their name from the uppermost polyp, a gas-filled bladder, or pneumatophore, which sits above the water and somewhat resembles an old warship at full sail. Man-of-wars are also known as bluebottles for the purple-blue color of their pneumatophores.

Purple Sea Squirt (Clavelina picta)

Purple Sea Urchin (Lytechinus variegatus)

Purple-tipped Sea Anemone (Condylactis gigantea)

Red-eared Sardine (Harengula humeralis) – this fish is called Pilchard in Bermuda.

Red Hind. Epinephelus guttatus. Shown on the March 12, 1979 Bermuda postage stamp.

Reefs. While coral reefs are common elsewhere, Bermuda is one of the northernmost areas in the Western Hemisphere. (But by no means the northernmost place in the world for coral reefs, as is commonly but mistakenly claimed, as there are cold-water and other coral reefs on the coastlines of Spain and Portugal throughout the northeast Atlantic, stretching north in the Irish sea, then due north, northwest and northeast all the way up to Norway). The coral Skolymia cubensis, not recorded until the 1970s, is now relatively common in Bermuda. Cold-water corals form a rich habitat for deep-water species hunted by fishing trawlers mostly from Ireland, Northern Ireland, Scotland, England, Wales, France and Norway. Coral reefs alone cover an area twice the length of Australia's Great Barrier Reef. Only in all the islands of Bermuda, the islands of the Bahamas including Harbour Island and at least five places in Scotland is the sand pink, but not because of the warm water corals. It is untrue to say that Bermuda's beaches have coarser sand. In fact, the sand in Bermuda is exceptionally fine. Bermuda's coral reefs, from where the forams come, are in better condition than many Bahamas reefs. Many Caribbean reefs have the disease known as YBD. By comparison, there has been only one recorded case of YBD in Bermuda recently. Local coral diseases are mostly BBD, less infected, the majority of them brain corals. Corals are the critical organisms in coral reefs formation because their calcium carbonate (limestone) skeletons create the framework of reefs that build up over thousands of years into a massive structure that supports the living corals and a great variety of other plant and animal life. Corals thrive in areas where strong wave action aerates the water, increasing the supply of food and oxygen. Waves also prevent silt from accumulating and suffocating the coral.

Reef Silverside, Rush Fry (Hypoatherina harringtonensis).

Reef Squid (Sepiotheuthis sepioidea)

Remora (sucker fish). On August 18, 2018 a woman swimmer was chased by a three-foot-long sucker fish for an hour in a bizarre game of tag that left her with a bite on her toe. Rachel Ann Garbett said the remora fish stalked her as she swam from a boat in the waters off Admiralty Park House in Pembroke and she was forced to take refuge on another boat.

Ringed Anemone (Bartholomea annulata)

Rock Beauty. Holacanthus tricolor. Shown on the March 12, 1979 Bermuda postage stamp above.

Rock Scallop. Spondylus ictericus.

Rose Coral (Isophyllia sinuosa).

Sand Dollar (Leodia sexiesperforata).

Sargassum Fish. Bermuda’s humble sargassum fish was thrust into the limelight in November 2015 as the star of a sequence in The Blue Planet series narrated by David Attenborough. The British Broadcasting Corporation sent three members of crew to the Island in 2013 when they spent one month filming the thumb-sized predators using filming technology so advanced it was not even available on the commercial market at the time. Producer Hugh Pearson, director of photography Doug Anderson and digital technician John Chambers, veterans of the Africa and Frozen series, accompanied a crew of Bermudians during their visit including LookBermuda’s Jean-Pierre Rouja who led the expedition as on-Island producer. Bermudians Harold Conyers, Chris Burville and Peter Flook were part of the operation acting as skippers and crew. The footage formed a sequence in The Blue Planet sub-series titled The Hunt. Pound for pound the sargassum fish is an absolutely incredible predator, it will swallow creatures larger than itself and it has a voracious appetite. It is like a combination between a pit bull and an anaconda. It is under two inches long but they will eat anything including each other.

Seahorses. Seahorses are rarely seen in Bermuda but three species have been reported locally, the Longsnout Seahorse (Hippocampus reidi), the Lined Seahorse (Hippocampus erectus) and the Dwarf Seahorse (Hippocampus zostera). They can be found in seagrass beds and algae-covered bottoms, where they wrap their tails around a plant for support and use their colouring as camouflage. Seahorses can also be seen on mooring lines and around docks. They are also found in floating mats of Sargassum seaweed. Seahorses are unlike other fish, as they don’t have scales. Instead they have bony plates covered by a thin skin. They also don’t have teeth or a fully developed digestive system. Seahorses eat small crustaceans and plankton by sucking the prey into their mouths and swallowing it whole. The Longsnout Seahorse has a long snout and a narrow body. It does not have projecting spines, filaments or fleshy tabs, giving it a smoother profile than other local species. It can range in colour from yellow to orange, brown or black and is sometimes two colours. It often has small brown or black dots on the body and white dots on the tail. These black spots are the key characteristic of this species.

Sea Pudding (Isostichopus badionotus).

Sea Sand Moss (Caulerpa taxifolia).

Sergeant major. Abudefduf saxatilis. Common in Bermuda waters, also throughout the Caribbean 900 miles south.

Sea grasses. Very important to the marine ecosystem. They link mangrove communities to coral reefs. The four species in Bermuda are Thalassia testudinum (turtle grass); Syringodium (manatee grass); Halodule wrightii (shoal grass, common) and Halophila decipiens (rare.

Seahorses. Three species have been recorded in Bermuda, Longsnout Seahorse (Hippocampus reidi); Lined Seahorse (Hippocampus erectus); and Dwarf Seahorse (Hippocampus zostera). None are endemic, now endangered or vulnerable and rarely seen nowadays in Bermuda, on the World Conservation Red List of Threatened Animals. They can be found in seagrass beds and algae-covered bottoms, where they wrap their tails around a plant for support and use their colouring as camouflage. Seahorses can also be seen on mooring lines and around docks. They are also found in floating mats of Sargassum seaweed. Seahorses are unlike other fish, as they don’t have scales. Instead they have bony plates covered by a thin skin. They also don’t have teeth or a fully developed digestive system. Seahorses eat small crustaceans and plankton by sucking the prey into their mouths and swallowing it whole. The Longsnout Seahorse has a long snout and a narrow body. It does not have projecting spines, filaments or fleshy tabs, giving it a smoother profile than other local species. It can range in colour from yellow to orange, brown or black and is sometimes two colours. It often has small brown or black dots on the body and white dots on the tail. These black spots are the key characteristic of this species. The Lined Seahorse also often has white dots on its tail. The back of this species is spiny, unlike the Longsnout Seahorse, and its snout is shorter – usually less than half the length of its head. The Lined Seahorse also has a thicker body than the Longsnout species. The Lined Seahorse often has white lines on its head and neck, and often has fleshy growths or tabs of skin on its head; these are the key characteristics of this species. The body colour can be grey, orange, brown or black and may include splotches of lighter colours. Both the Lined and Longsnout Seahorse are about 6 - 10 cm (2.5 - 4 inches) tall, with the largest specimens reaching 15 cm (6 inches). The Dwarf Seahorse is quite tiny – the maximum recorded adult height for this species is reported to be 2.5 cm (1 inch). It has a short snout and can be beige, yellow, green or black and may have dark spots or white patches. This species often also has thread-like filaments attached to it. In Bermuda, the Longsnout and Lined Seahorses are both protected under the 2003 Protected Species Act. The Dwarf Seahorse has not been seen in Bermuda since 1905 and is assumed to have been extirpated (become locally extinct).

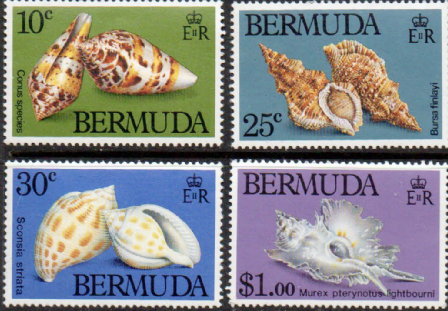

Sea shells. The largest and most complete collection of Bermuda shells to be found anywhere in the world was donated in October 2001 to the Natural History Museum at the Bermuda Aquarium, Museum and Zoo. They were collected by retired banker the late Jack Lightbourn and his late colleague and friend Arthur Guest since 1965. There are about 7,700 species in all in the collection, with several endemic. One particularly interesting live shell is the Atlantic Trumpet Triton found in local waters. A Bermuda 40c stamp was issued to note it in philately

1982 Bermuda Sea Shells postage stamps

Atlantic Trumpet Triton Bermuda postage stamp

Seals. Not a Bermuda animal but several were imported for the Bermuda Aquarium and have seen bred.